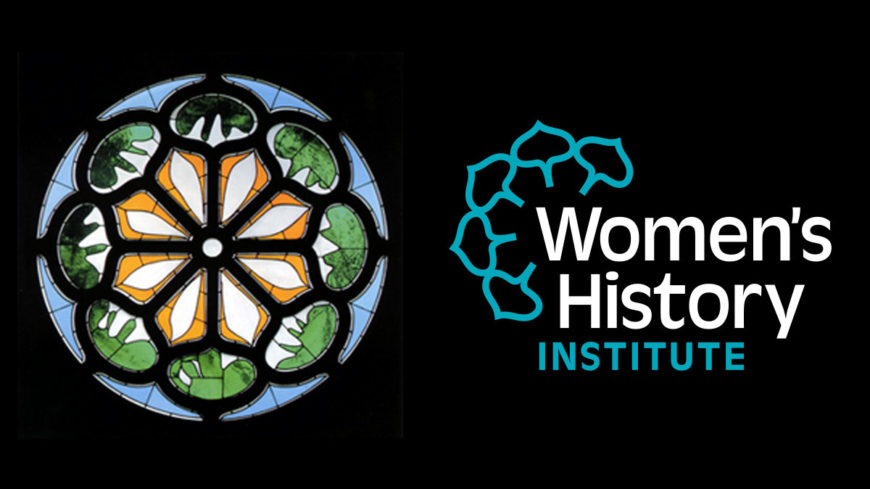

The Story Behind the Women’s History Institute Logo

The pieces of glass that comprise the rose window at Union Church in Pocantico Hills (pictured above, left) are unique, in shape, density, texture, and hue. They are as distinctive as the facets of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s life.

Commissioned in her memory and dedicated on Mother’s Day in 1956, “La Rosace” has come to symbolize a new way of thinking about the accomplishments of women like Abby Rockefeller and the roles they play.

By choosing aspects of the window for the logo of the Women’s History Institute of Historic Hudson Valley (HHV), “we found a way to speak to the work we already do, and broaden the direction of the Rockefeller legacy,” said Elizabeth Bradley, HHV’s Senior Director of Programs and Engagement. “We are stewards of their house and church, but the Rockefeller influence is felt all over the world. So, too, is the influence of women who shaped the Hudson Valley.”

HHV’s interpretations of Philipsburg Manor, the Van Cortlandt estate, and Sunnyside in particular focus on women’s work, Bradley said, and the Women’s History Institute (WHI) logo could have incorporated a spinning wheel or a sampler, objects that typified a women’s work of the time period. “But those things wouldn’t be unique to us at HHV,” she said.

Instead, the founders of the Institute felt that the window reflects Abby Rockefeller’s defining traits, including her patronage of the arts and her support of Henri Matisse, the artist her children chose for its design.

“We love that Abby was Matisse’s patron,” Bradley said. “She flipped the traditional role for a woman. She wasn’t just a hostess for a powerful and influential family. She was an incredible mover and shaker in the world of modern art.”

The logo of the Women’s History Institute at Historic Hudson Valley.

Abby not only collected Matisse’s work and entertained him at her Manhattan apartment, she supported modern artists and instilled a love of art in her son, Nelson. Along with Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan, she founded the Museum of Modern Art in 1929.

Matisse died shortly after he finished his model for the window, but before it could be fabricated. Knowing that it was his last work, his daughter, Marguerite Duthuit, saw it through to its completion. “His daughter ensured the work made its way to a glazier and eventually to its place at Union Church,” said Bradley, who added that the information about Ms. Duthuit’s involvement wasn’t initially known.

“That detail made it doubly wonderful,” she said. “So many women, daughters and mothers and wives, shepherded the window to the position it has today. It’s so symbolic of what the Founding Committee and the Institute does for us at HHV.”