A Day In the Life With Ann Hoffman

“I am sorry to say school grows every day more irksome to me,” 15-year-old Ann Hoffman wrote to her father on February 19th, 1805. From November 1804 to April 1806, Ann studied at Madame Grelaud’s school in Philadelphia, where she spent hours each day learning French – much to her chagrin. “I ought to acquire the french language perfectly,” she lamented, “to repay me the many doleful nights & days I have spent within the walls of Mrs. Gerlaud’s school.”i

Her letter reflects the frustration a teenage schoolgirl felt at a moment in American history when some young women were afforded the opportunity to study at finishing schools but often denied access to the more rigorous curricula common at men’s schools. The central grievance Ann airs in her letter was not that she was required to learn: it was that she exclusively learned French, music, and sewing – disciplines that would prepare her for domestic life as a middle- or upper-class wife.

In her letter, Ann describes a school day in a nation experiencing growing pains. While Ann attended school, the newly independent U.S. struggled to reconcile the egalitarian ideals expressed in its founding documents with elites’ desire to secure their spot at the top of an emerging social hierarchy. Women’s schooling negotiated fraught social dynamics, offering young white women inclusion in formal education on the terms of a society that largely excluded them from public life and excluded women of color from schooling altogether.ii

Spending the day with Ann reveals the tensions that underscored women’s educational experiences in the early Republic. Her day began on “the hour of rising.”

7 AM to 9 AM: “I do nothing.”

In the first hours after she woke up, Ann reported, “I do nothing.” This idleness might have bothered her letter’s recipient, her father and prominent New York judge Josiah Ogden Hoffman. In his letters to Ann, Judge Hoffman often emphasized the importance of hard work. He wrote, “At your age, the person is to be formed and its defects lessened if not perfectly cured, every year.”iii The activities Ann completed at school, he believed, would be essential in molding her into a well-mannered, upper-class young woman.

Judge Hoffman’s thinking aligned with Enlightenment philosopher John Locke’s argument that, at birth, children’s slates were blank, suggesting that influential adults could shape children’s characters to fit certain desirable qualities.iv For young women, however, education’s brush did not paint on a completely blank slate, absent good or bad qualities: it painted over deficiencies preinstalled on the female canvas. “Manners and personal carriage,” Judge Hoffman explained, “are essential ornaments to your sex. They are necessary to ours, but to yours, they are peculiarly requisite. You have defects in your person – now is the time to remedy them.”v

Ann’s declaration that she did nothing for multiple hours every day suggests she wasted time at a moment in her life when her future depended on what she did do during her hours at school. Judge Hoffman believed that central to crafting Ann’s “manners and personal carriage” was the foreign language she learned. “Study your french,” he urged, “do not lose a moment.”vi

Figure 1 The Gothic Mansion: Illustrated in The Port Folio, Volume V (February 1811), 125, in Mary Johnson, “Madame Rivardi’s Seminary in the Gothic Mansion,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History of Biography 104, no. 1 (1980), 13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20091428.

9 AM to 12 PM: “the French master stays.”

In almost every letter Judge Hoffman wrote to Ann while she attended Mme. Grelaud’s school, he inquired about her progress in learning French. “With the knowledge of the french language,” he explained in one letter, “you are expected to display the grace, ease and beauty of a real french Lady.” vii

Though the French Revolution strained America’s diplomatic relationship with France, American elites in the 1790s and early 1800s adopted elements of French culture to enhance the fashionable personas they aimed to project. Meanwhile, many French aristocrats who fled the Revolution immigrated to Philadelphia and, capitalizing on American elites’ demand for French culture, founded women’s boarding schools.viii At schools like Ann’s, upper-class families paid large sums in exchange for their daughters’ mastery of the French language.

As schooling became available to women across the middle class in the early 19th century,ix learning French distinguished an upper-class girl’s education. Middle-class women studied the basics of reading, writing, and geography, skills that prepared them to help with family business.x The French that Ann learned at school, in contrast, served the dual purpose of signaling her family’s wealth and preparing her to enter a cosmopolitan elite society that valued French culture highly after her graduation.

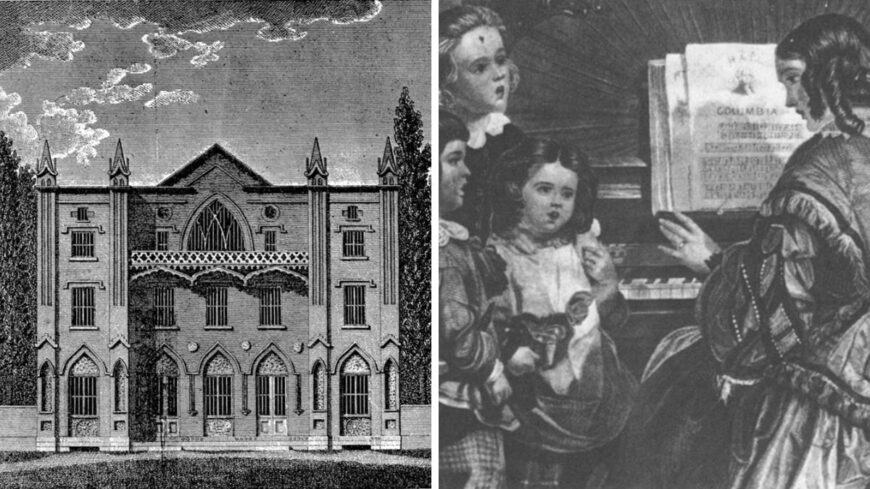

Figure 2 A Mother Plays for Her Children. Women did teach piano and voice. Hail Columbia, aquatint with etching from the November 1860 edition of Godey’s, in Julia Eklund Koza, “Music and the Feminine Sphere: Images of Women as Musicians in ‘Godey’s Lady’s Book’, 1830-1877,” The Musical Quarterly 75, no. 2 (1991): 115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/742197.

12 PM to 2 PM: “I practice my music.”

For two hours in the afternoon, Ann practiced the piano. Like the French she studied, her music education prepared her for life after graduation. As the egalitarian ideals of democracy permeated early American culture, etiquette manuals emphasized the importance of women’s intellect equaling men’s.xi Becoming an educated “woman of sense,” however, did not mean preparing to perform the same social roles as men. Rather, education reformers of the period argued, schooling would equip women to better serve their husbands.xii

“Personal charms,” The Female Instructor warned, “may please for a moment; but the more lasting beauties of improved understanding, and intelligent mind, can never tire.”xiii Musical performance captured the intersection of this advice. While Ann played piano, she would both display a talent to charm her audience and demonstrate the intellectual accomplishment of learning to read and play music. In addition to helping a woman win and maintain a husband’s affection, playing music could aid her in raising virtuous children. As a young woman played piano at school, she learned the value of self-discipline, which she would later instill in her children as she played piano for them or taught them how to play.xiv

Though learning piano offered some women a means of self-expression, Ann felt the strain of an education tailored to societal expectations rather than her own interests. She emphasized with a hint of frustration, “[these] you see are the two things I learn french & music.”

Figure 3 Needlework by either Catharine or Sarah Irving (c. early 1830s) in various kinds of embroidery with raised/stumpwork, and wax heads and hands. SS.63.625.

2 PM to 5 PM: “I… sit & sow.”

After a break for lunch and her music lessons, Ann noted that she spent time sewing. Women’s schools often offered instruction in needlework, in exchange for an additional fee.xv Ann’s mention of sewing indicates that Judge Hoffman was willing to pay this fee on top of her tuition and boarding expenses. At Mme. Grelaud’s Ann likely continued the process of learning needlework that she had begun at Miss Hay’s school in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where she studied from 1800 to 1803 for a $120 annual fee, about $3,200 today.xvi Over Ann’s six years of formal schooling, Judge Hoffman likely paid hundreds of additional dollars to supply Ann with needlework instruction and the necessary cloth.

In the early Republic, making cloth required a labor-intensive process of harvesting linen and cotton plants, spinning their fibers into thread, and weaving the threads together. Throughout the first decades of the 1800s, this process increasingly relied on land expropriated from Native Americans and the labor of enslaved people to cultivate that land.xvii As white female students embroidered cloth, they asserted their distance from the process of its making. Rather than laboring in a linen field or weaving cloth for use as clothing or household furnishings, they embroidered for the purpose of displaying their work. Their needlework signaled their upper-class identity, conveying that they had the money to pay for the materials and the time to dedicate to the craft.

Increasingly in the early 1800s, American mercantile and professional elites made their fortunes by speculating on Native lands and enhanced their wealth by relying on the unpaid labor of enslaved people, and they used their money to fund their daughters’ educations. When Judge Hoffman wrote to Ann at Miss Hay’s in 1800, “it is my wish to gratify you in every reasonable indulgence,” the U.S. census from that year reflected two enslaved people in his household.xviii

5 PM to 9: “I cannot read.”

In the evening, Ann complained, “I cannot read for the little girls are round the table studying their lessons, & they make too much noise.” In another letter, Ann mentioned she planned to read Charles Rollins’ Ancient History.xix Because her schedule at Mme. Grelaud’s did not allow time for studying history, Ann might have pursued her interest in the subject after her school day had ended, becoming frustrated when the disruptive environment interfered.

Ann’s education exists at a turning point in the history of women’s education. By the time her daughter, Emma, attended school in 1828, women’s curricula had changed. Emma studied history during her school day and left behind seventeen booklets of detailed notes, and she did not struggle with the boredom that had filled Ann’s days at Mme. Grelaud’s. She wrote to her grandfather, “I study very hard and should try to improve myself. I study French Elocution Geography Grammar History Rhetoric Arithmetic.”xx

As the women of Ann’s generation grew up and founded their own schools, they introduced rigorous curricula that mirrored men’s schooling, and the decorative arts that Ann had studied gradually fell out of fashion as they became synonymous with superficiality. Emma wrote, “I learnt drawing the first quarter, but Mother thought I did not improve so I gave it up.” As Emma attended school in 1828, her mother headed the boarding department at Albany Female Seminary.xxii

While Ann worked there, she might have encouraged her students to pursue the interests she hadn’t been able to when she attended finishing school.

Years earlier, Ann finished her day at Mme. Grelaud’s. At 9 PM, she wrote, “I go to bed… with a heavy heart.”

Grace Ellis was a 2023 Women’s History Institute Summer Research Fellow. Ellis is majoring in American Studies with a concentration in Public Humanities. She has worked as a student archivist for the Beinecke Library’s special collections and is the lead producer of the Yale Daily News history podcast Footnotes.

iAnn Hoffman to Josiah Ogden Hoffman, 19 February 1805, Historic Hudson Valley, Manuscript Collections, Hoffman Family Collection, folder HF3013.

iiMary Kelley, Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 31.

iiiJosiah Ogden Hoffman to Ann Hoffman, 3 June 1800, Historic Hudson Valley, Manuscript Collections, Hoffman Family Collection, folder HF3022.

ivMary Lynn Stevens Heininger, “Children, Childhood, and Change in America, 1820-1920, in A Century of Childhood 1820-1920 (Rochester, New York: The Margaret Woodbury Strong Museum, 1984), 2-3.

vJosiah Ogden Hoffman to Ann Hoffman, 21 June 1801, Historic Hudson Valley, Manuscript Collections, Hoffman Family Collection, folder HF3022.

viJosiah Ogden Hoffman to Ann Hoffman, 23 February 1804, Historic Hudson Valley, Manuscript Collections, Hoffman Family Collection, folder HF3022.

viiJosiah Ogden Hoffman to Ann Hoffman, 28 January 1804, Historic Hudson Valley, Manuscript Collections, Hoffman Family Collection, folder HF3022.

viiiMary Johnson, “Madame Rivardi’s Seminary in the Gothic Mansion,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History of and Biography 104, no. 1 (1980), 10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20091428.

ixKelley, Learning to Stand and Speak, 23.

xDianne Ashton, Rebecca Gratz: Women and Judaism in Antebellum America (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997), 36.

xiSusan Branson, These Fiery Frenchified Dames: Women and Political Culture in Early National Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 13.

xiiSweet, Leonard I. “The Female Seminary Movement and Woman’s Mission in Antebellum America.” Church History, vol. 54, no. 1, 1985, pp. 41–55.

xiiiThe New Female Instructor or Young Woman’s Guide to Domestic Happiness (London: Rosters Ltd., 1988), first published 1834, 3.

xivCraig H. Roelle, The Piano in America, 1890-1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989): 14.

vJohnson, “Madame Rivardi’s Seminary in the Gothic Mansion,” 22.

xvi“Miss Hay’s Boarding School for Young Ladies,” New Brunswick Advertiser, 27 April, 1803.

xviiSven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York: Vintage Books, 2015), 105.

xviii“United States Census, 1800,” database with images, Family Search, entry for Josiah O. Hoffman, 1800, linked here (accessed 16 August 2023).

xixAnn Hoffman to Josiah Ogden Hoffman, 20 December 1804, Historic Hudson Valley, Manuscript Collections, Hoffman Family Collection, folder HF3013.

xxEmma Hoffman Nicholas to Josiah Ogden Hoffman, 31 December 1828, Historic Hudson Valley, Manuscript Collections, Hoffman Family Collection, folder HF 3019.

xxiJohnson, “Madame Rivardi’s Seminary in the Gothic Mansion,” 37.

xxii“Education,” Albany Argus, 22 August, 1828. Linked here (accessed 15 August 2023). See Appendix IV for an image of the advertisement.