Mad Dogs in the Archives: Finding Sound Medical Advice in 18th-Century Home Remedies

by Rivka Salhanick

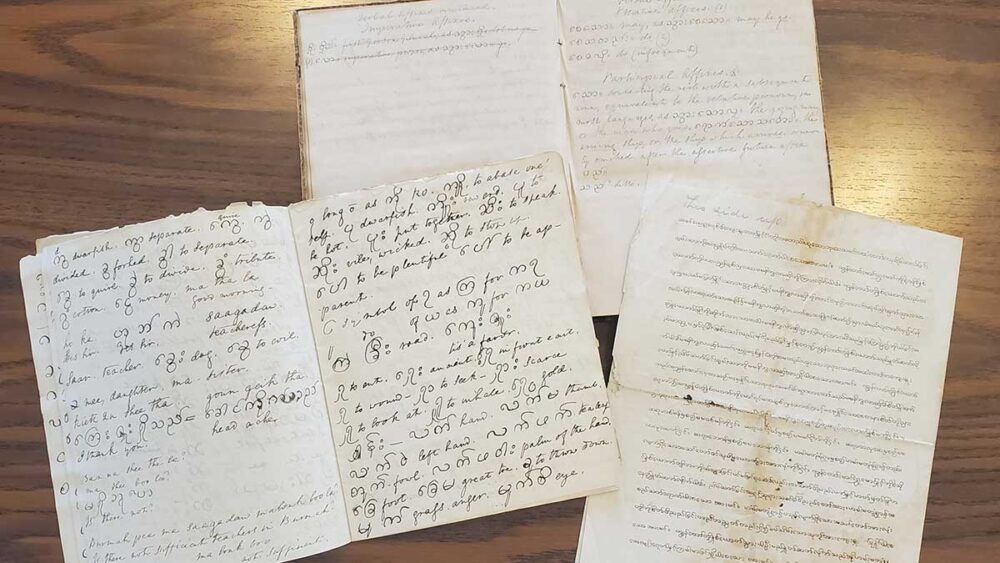

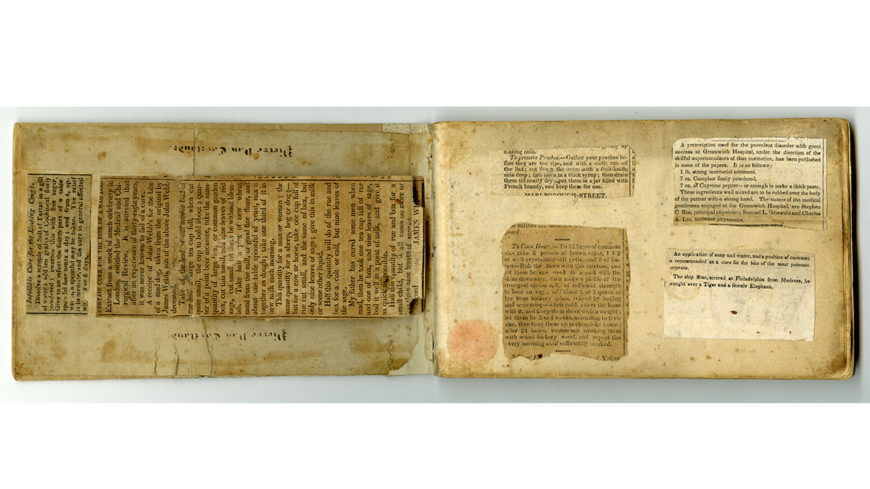

One of the treasures in the library of Historic Hudson Valley is the manuscript receipt book of Anne Stevenson Van Cortlandt (1774-1821), the second wife of Pierre Van Cortlandt II. The receipt book is a compilation of both the recipes from Anne’s mother, Magdalena Douw Stevenson (1750-1817), as well as Van Cortlandt’s own additions. The small notebook-sized manuscript also holds many home remedies and medical advice, in a combination of newspaper clippings and handwritten notes.

The receipt book opens with a newspaper clipping for a “Certain Cure for the Bite of a Mad Dog”, with a remedy that appears to have been pulled from the Medical and Chirurgical Review in London. The bite of a mad dog, or hydrophobia as it was commonly called, is what we know today as rabies. The rabies virus is carried in a rabid animal’s saliva. When a person or animal is bitten by a rabid animal, the virus infects the peripheral and central nervous system. The beginning symptoms include fever, pain in the area of the bite, as well as hydrophobia, which is a difficulty swallowing that causes a fear of all liquids. As the disease progresses, it eventually causes paralysis, muscle spasms, and nearly always death.

Getting bitten by a mad dog was not unusual in the 18th and 19th centuries. Many contemporary receipt books and books of medical advice held multiple cures for the bite of a rabid dog. The Stevenson-Van Cortlandt manuscript itself holds three remedies for this injury, a surprisingly high number of cures for a volume of this size. Below is an excerpt from a “Certain Cure for the Bite of a Mad Dog” presented at the opening of the manuscript:

“Take of the leaf of the tender bud of rue half a large tea cup full, when cut quite small… add nine leaves of red sage, cut small, let them be without blemish. Take half a pint of new wheat meal from the mill, or good fine flour, and about one table spoonful of yeast. Mix it together as a dough; take one third of it in new milk each morning[.]” [1]

The use of rue is repeated in the second remedy for the bite of a mad dog, in another newspaper clipping pasted into the back of the book. This remedy advises to use “Six oz. filings of pewter, 6 oz. rue, 4 oz. garlic, 4 oz. mithridate or Venice treacle.”[2]

Evidently, the use of the plants rue and sage for a mad dog bite was not uncommon, and a similar remedy is listed in The Compleat Housewife, or, Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion, a preeminent housewife’s manual of the eighteenth century, that famously ran to eighteen editions first in London and then in America. The Compleat Housewife advises the healer to use similar ingredients: “[t]ake sage leaves and rue, of each a good handful, 2 or 3 heads of garlick, 4 Pennyworth of the best treacle, [and] a handful of the smallest shavings of tin and Pewter[.]”[3]

The overlap of rue, or Ruta graveolens, in these three remedies, and many others, is worthy of note. Rue has been used for centuries as a cure for certain ailments. Dioscorides, a Greek physician of the first century, describes how rue was used as a “counterpoison of serpents”, and it was also thought to counter infection.[4] Nicholas Culpeper writes in his treatise, The Complete Herbal, a famous and well-used bible of herbs and their uses, that “the seed [of rue] taken in wine, is an antidote against all dangerous medicines or deadly poisons… it resists poison and cures venomous bites.”[5] Other sources record the use of rue as an antispasmodic, which may have helped alleviate the muscle spasms associated with rabies.

Additionally, recent medical research suggests another way that rue may have been medically effective at reducing some of the symptoms associated with the rabies. A 2014 research study conducted in South Africa aimed to discover whether the use of rue, for common ailments such as fever, toothaches, earaches, and rheumatisms, actually has scientific efficacy. Data corroborated that a leaf menthol extract of R graveolens effectively had antinociceptive (pain reducing), antipyretic (fever reducing), and anti-inflammatory effects. These findings supported the use of rue by traditional medical practitioners in South Africa who use the herb to reduce fever and manage pain. Consequently, it is possible that the use of rue for rabies may have helped reduced the fever, as well as the pain and inflammation at the site of the bite.

Although the centuries-old herbal remedies used by housewives may seem medically irrelevant, there is validity and efficacy in many of their medical advice. The ability to bridge the gap between 18th-century home remedies and 21st-century medical research opens a new opportunity for exploration into every day practices in the colonial home.

Rivka Salhanick was a 2018 Women’s History Institute Summer Research Fellow at Historic Hudson Valley. She is a graduate of Yeshiva University, where she currently serves as a Teaching Assistant.

[1] Stevenson-Van Cortlandt Cookery Manuscript V 2443. Historic Hudson Valley Archive.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Smith, Eliza. The Compleat Housewife, or, Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion. London, s.n. 1729. pg. 241.

[4] Tobe, J. Proven Herbal Remedies. Provoker Press. Canada 1969. pg.38.

[5] Culpeper, Nicholas, Culpeper’s Complete Herbal. Foulsham & Co. Ltd. [n.d]. pg. 304-305.