Who Really Invented Christmas: Washington Irving or Charles Dickens?

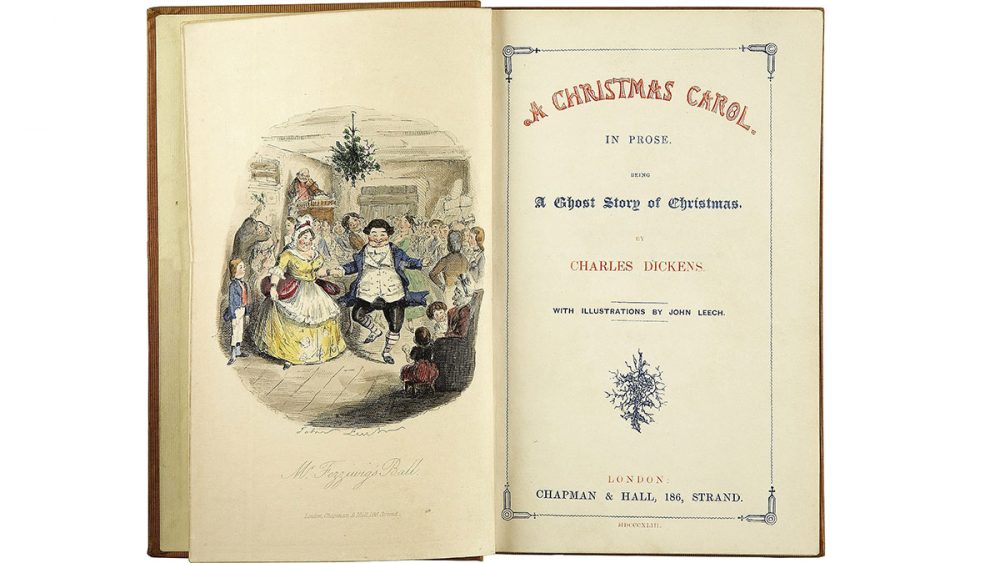

There’s a new movie in the theaters, just in time for the holidays. The Man Who Invented Christmas, starring Dan Stevens of Downton Abbey fame, is a rollicking period piece about how Charles Dickens came to write A Christmas Carol in 1843 and thus to invent the holiday as we know it, right down to the bah humbugs and figgy puddings.

But there’s just one problem with that premise: Dickens didn’t invent Christmas. If any author can lay claim to inventing this venerable holiday, it’s Washington Irving. Most people think of Halloween when they think of Irving: thanks to the Headless Horseman, our first ghost storyteller has become the mascot of the spooky season. But that famous spectral Hessian actually made his appearance in print alongside a set of stories about the customs of a rural English Christmas. In The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, the book that first introduced “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” Irving (as alter ego Geoffrey Crayon), waxes rhapsodic over the traditional pleasures of Christmas at a fictional country estate called Bracebridge Hall.

Fine, you say, both authors liked Christmas, what’s the big deal?

Irving’s book came out in 1820, when Charles Dickens was just eight years old.

How about some forensic evidence? Christmas at Irving’s Bracebridge Hall is overseen by Squire Bracebridge, a genial host who likes to eat, dance, and encourage his guests in “the old games of hoodman blind, shoe the wild mare, hot cockles, steal the white loaf, Bob apple, and snap dragon.” This sounds a lot like Samuel Pickwick, the hero of Dickens’ first novel, The Pickwick Papers, which was published 16 years later (before A Christmas Carol): “when they were all tired of blind-man’s buff, there was a great game at snap-dragon.” Both characters call for a bowl of wassail, the potent wine-based punch: Squire Bracebridge’s 1820 wassail is “highly spiced and sweetened, with roasted apples bobbing about the surface” while Samuel Pickwick’s 1836 drink features “hot apples… hissing and bubbling with a rich look, and a jolly sound, that were perfectly irresistible.”

Quick: who wrote about mince pies first? Answer: Irving.

Not convinced? Let’s talk about ghosts, especially that old chain-rattler made famous by many a made-for-TV movie, Jacob Marley:

And then let any man explain to me, if he can, how it happened that Scrooge, having his key in the lock of the door, saw in the knocker, without its undergoing any intermediate process of change—not a knocker, but Marley’s face.

Dickens’ Jacob Marley, with his penchant for appearing on fireplace tiles and door knockers, could just as easily have been spotted in the room Geoffrey Crayon stays at in Bracebridge Hall, which was “paneled…with cornices of heavy carved work, in which flowers and grotesque faces were strangely intermingled.” In another Irving story from 1824, “The Adventure of the Mysterious Picture,” the narrator blames his “perfidious dinner” for his nightmares and ghostly visions:

I was hag-ridden by a fat saddle of mutton; a plum pudding weighed like lead upon my conscience; the merry thought of a capon filled me with horrible suggestions; and a devilled leg of a turkey stalked in all kinds of diabolical shapes through my imagination.

Nineteen years later, a ghostly Marley asks Scrooge why he doesn’t believe in him, and gets a rather familiar reply:

“Because,” said Scrooge, “a little thing affects them. A slight disorder of the stomach makes them cheats. You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

Dyspeptic Scrooge himself can be found lurking on the pages of “Bracebridge Hall,” the embodiment of Geoffrey Crayon’s warning to those who reject charity at Christmas:

He who can turn churlishly away from contemplating the felicity of his fellow-beings, and can sit down darkling and repining in his loneliness when all around is joyful… wants the genial and social sympathies which constitute the charm of a merry Christmas.

There was no churl as lonely as Ebenezer Scrooge.

If all this doesn’t add up, you might roll the tape: or in this case, the fan mail. Dickens and Irving kept up a friendly correspondence, and a few letters are all that’s needed to show how completely the English author had absorbed – memorized, even – the imagery of his American predecessor. “Diedrich Knickerbocker I have worn to death in my pocket, and yet I should show you his mutilated carcass with a joy past all expression,” Dickens wrote of his copy of Irving’s Sketchbook, adding, fancifully, “I wish to travel with you… down to Bracebridge Hall.” Unable to make this fictional pilgrimage, he confessed in another letter that he “holds communion with [Irving’s] spirit oftener, perhaps, than any other person alive.” A Christmas Carol is the clear product of this communion.

Did Irving invent Christmas? Let’s just call him the true Ghost of Christmas Past.