Textiles Talk: A Mystery Gown’s Connection to Hudson Valley Women

I’ve always considered textiles to be a rich source in uncovering women’s untold stories. What a woman wore can tell the historian a lot about what her life looked like: did she wear primarily practical garments, necessary for manual labor, or was she clad in luxurious fabrics, indicating a higher socioeconomic status? Did she keep up with the latest fashions, or do her garments show evidence of repairs, prolonging the life of one dress far past its moment in the trend cycle? Furthermore, the level of intergenerational care required to preserve clothing across the centuries inevitably produces an uneven body of evidence: a cotillion gown belonging to a wealthy young woman from a prominent family is far more likely to be preserved than the day dress of a domestic servant. One particular textile piece in the Historic Hudson Valley collection demonstrates exactly what makes fashion history such a rich field for illuminating the unique experiences of women.

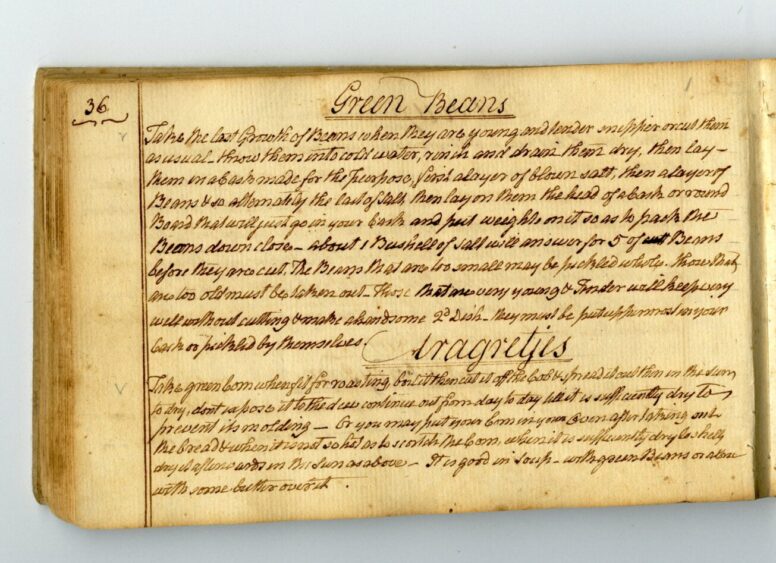

Labeled in the collections as a wedding dress collected by Ann Van Cortlandt, this pink satin brocade gown exhibits a confusing collection of seemingly disparate design and construction choices. The silhouette is late 19th century, while the three-quarter sleeves and open front, both lace embellished, are reminiscent of the late 18th. However, the garment seems to have been constructed using a sewing machine, which would not have been commercially available until the second half of the 19th century. The 1998 MoMA exhibition entitled “The Ceaseless Century” highlights what they consider to be the long shadow cast by 18th-century fashion into the 20th century and beyond. The exhibit included a number of 19th century dresses that incorporated 18th century features such as the polonaise and the open robe in what curator Richard Martin describes as a “willful act of hyperbole and exaggeration” that brought 18th century fashion into the ‘modern’ 19th century which both reviled the old regime and looked upon its ostentation with nostalgia.1Similar design features have led curators at Historic Hudson Valley to consider that the gown in our collection might not be a wedding dress but could be an 18th-century style gown used as a costume for a centennial ball in the late 19th century. A similar gown was exhibited in “The Ceaseless Century,” a bubblegum pink concoction from the 1870s with exaggerated, almost costume-like 18th-century features that highlights both the aesthetic and nationalistic aspects of 18th-century revivalism in the context of centennial era nostalgia for the American Revolution.2

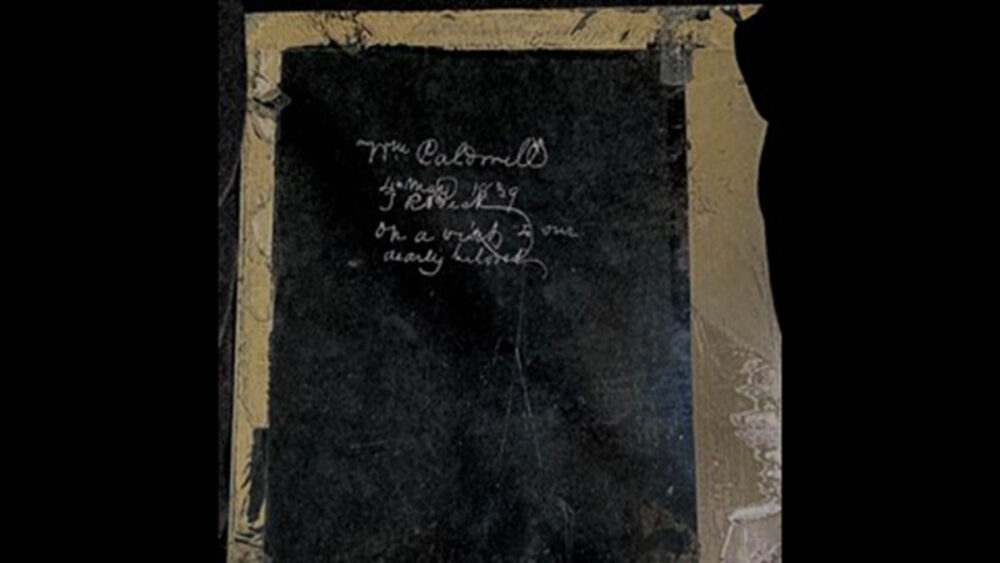

Beginning with the Centennial Exposition in 1876, the last quarter of the 19th century was host to a number of commemorations of the 100-year anniversaries of Revolution-era accomplishments. April 1889 found New York City commemorating the 100th anniversary of Washington’s inauguration with three days of parades, balls, and dinners. Though it can’t be proven that the dress in the Historic Hudson Valley collection was worn at one of these events, newspaper descriptions of the dresses worn to the centennial ball at the Metropolitan indicate features in common with Historic Hudson Valley’s gown. Furthermore, one particular attendee has a special connection with Historic Hudson Valley’s collection.

Julia Grinnell Storrow was born in 1847 to Sarah Paris Storrow, niece of Washington Irving. Passing her childhood in France, the family moved to the Hudson Valley in the early 1860s, less than a mile from Sunnyside, where Julie and her sisters Susie and Katherine were frequent visitors to their aunts Kate and Sarah Irving. Julie next appears in the historical record in 1868, as the newlywed wife of Stephen Van Rensselaer Cruger, of the prominent Cruger and Van Rensselaer families. Mr. Cruger not only possessed an enviable pedigree, but was also a recent war hero and would go on to become an influential member of the Republican Party in New York.

Mr. Cruger was on the official committee for the 1889 centennial. Julie, as his wife, had her own unofficial role to play. She danced in the centennial quadrille, for which the selection of dancers was a point of contention in the leadup to the event. According to the Illustrated Program of the Centennial Celebration published at the time, the quadrille was originally conceived as an attempt to closely imitate George Washington’s inaugural ball 100 years earlier. Therefore, a lady’s inclusion in the dance relied on her natal family’s pedigree, which outraged prominent men with wives who were excluded on the basis of their comparatively low birth. In the end, some dancers were replaced to placate the aggrieved parties.3 This conflict indicates the power accorded to women as wives in Gilded Age high society: a woman of negligible social standing could be elevated to the same position as a woman from the old families by virtue of her husband’s connections.

Julie is a perfect example of this phenomenon: though not from an old New York family herself, her marital connections to the Crugers and Van Rensselaers is what resulted in her inclusion in not only the quadrille, but high society in general. Being the wife of such a prominent man came with its own set of expectations and responsibilities, of which fashion was a significant part, as indicated by this thorough description of Julie’s gown for the Centennial Metropolitan Ball:

“Mrs. Stephen Van Rensselaer Cruger appeared in a pale yellow crepe de chine gown, falling in Grecian folds, and of marvelous beauty. It was trimmed with an abundance of golden lace, and had a majestic train of yellow plush sweeping from the low-cut corsage to the floor. From the pretty yellow satin shoes to the golden ornaments in her hair, and the girdle of gilt cord about her waist, everything matched, even to the corsage bouquet of yellow roses.”4

Extensive newspaper coverage of the gowns worn by Julie and other prominent wives illustrates the spotlight placed on women rather than their husbands during society events. Therefore, women like Julie had a significant responsibility to present themselves in a way that projected the right image. However, it was also possible for the ambitious to leverage that attention for personal gain. Though elevated to her high status by an advantageous marriage, Julie was able to use her position as a springboard for accomplishments typically unheard of for a high society wife. Julie’s later life was characterized by the publication of upwards of ten successful novels. By the time of her husband’s death in 1893, she was a celebrity in her own right. My fellowship research will highlight Julie’s extraordinary accomplishments and examine the uniquely public and independent life she built for herself on the back of her socio-marital connections.

Chelsea Laurik was a 2024 Women’s History Institute Summer Research Fellow.Ms. Laurik is a third-year undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, majoring in History. She is also an active member of the University of Edinburgh Savoy Opera Group, University of Edinburgh Footlights, University of Edinburgh Singers, and was the recipient of the Robertson International Scholarship (University of Edinburgh) awarded on academic merit.

[1] Richard Martin, The Ceaseless Century: 300 Years of Eighteenth-Century Costume, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), 53.

[2] Martin, The Ceaseless Century, 56.

[3] Illustrated Program of the Centennial Celebration, (New York, J. S. Ogilvie Publisher, 1889), 6.

[4] “A Marvel Among Balls” (The Sun, April 30, 1889), 7.