Stories of Maternal Grandeur: Girlhood and Motherhood in the Archives of Historic Hudson Valley

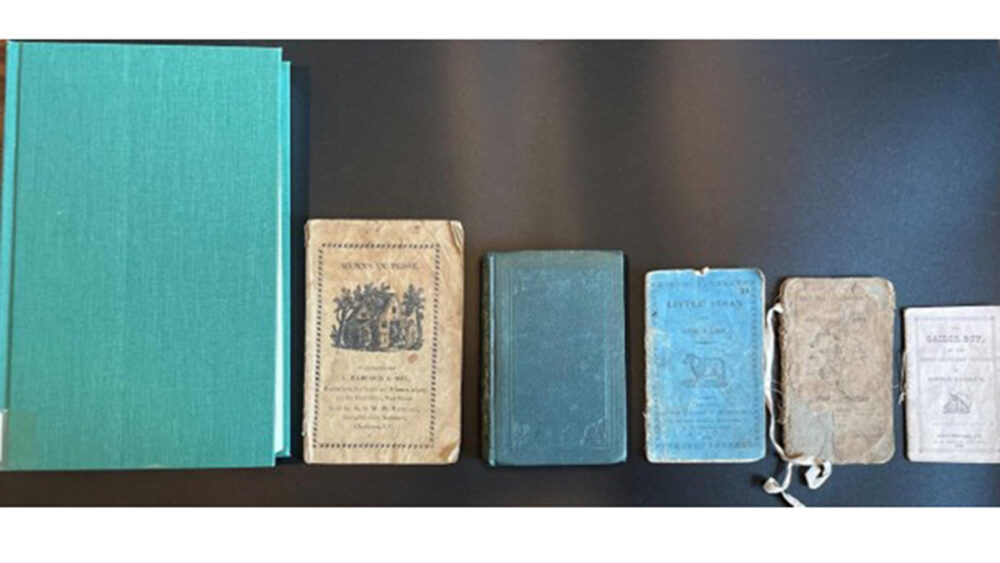

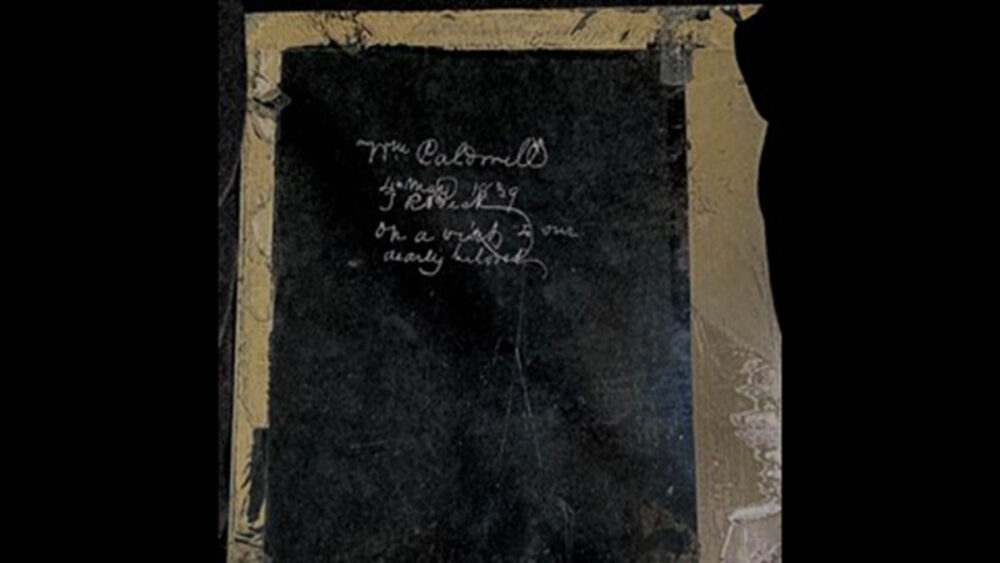

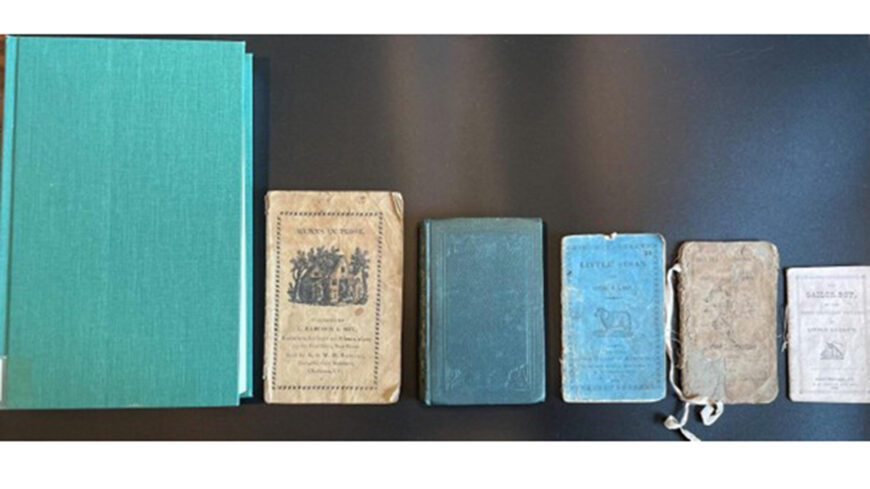

Do you remember the books your parents read to you as a child? As a young girl, Little Bear, Curious George, Narnia, and Anne of Green Gables were some of my favorites. I would snuggle up to my mom and lose myself in the vast, fictional worlds created for small folks. When I look back at those same tales now, I see they are full of moral undertones, some more transparent than others: don’t bully your peers, listen to your parents, clean up your messes, etc. Most children’s literature contains some type of moral advice that blends into the story, often subconsciously consumed. The same messages appear in 19th-century literature, which mostly provided educational, vocational, and moral lessons for children that reveal to historians the types of adult society wanted young people to grow into. My interest in girlhood and motherhood led me to the historic literature collection at Historic Hudson Valley, where I fell upon an array of tiny, miniature books created for children in the chilly archives where they lay, preserved in a rectangular banker’s box. These little writings from the 19th century attempted to mold and shape young girls into perfect adult women, focusing on their vocation as wives and mothers. They display the maternal expectations placed on women in the 18th and 19th centuries and how this translated to the daily experiences of real-life mothers.

“The mother loveth her little child; she bringeth it up on her knees; she nourished its body with food; she feedeth its mind with knowledge; if it is sick, she nurseth it with tender love; she watcheth over it when asleep; she forgetteth it not for a moment; she teacheth it how to be good; she rejoiceth daily in its growth.”1

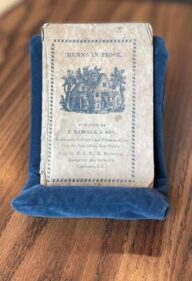

The above verses come from a small hymn book, published in 1819 in New Haven, Connecticut, titled, “Hymns in Prose,” published by J. Babcock and Sons.2 The stories portray women as almost exclusively wives and mothers, ushering girls into womanhood with the goal of marriage and then motherhood as their ultimate vocation. Books like these reveal the pressures placed on young girls as well as the maternal ideal projected in this time, an archetype that differed from earlier models of motherhood. The themes in children’s literature reflected shifting beliefs about both children and gender roles in the mid-18th and 19th centuries.

The above verses come from a small hymn book, published in 1819 in New Haven, Connecticut, titled, “Hymns in Prose,” published by J. Babcock and Sons.2 The stories portray women as almost exclusively wives and mothers, ushering girls into womanhood with the goal of marriage and then motherhood as their ultimate vocation. Books like these reveal the pressures placed on young girls as well as the maternal ideal projected in this time, an archetype that differed from earlier models of motherhood. The themes in children’s literature reflected shifting beliefs about both children and gender roles in the mid-18th and 19th centuries.

Earlier, colonial worldviews of childhood understood children as willful, stubborn, and born naturally sinful, informed in part by the religious understandings of original sin. Fathers played the most significant role in the raising of the child, responsible for breaking the will of their inherently corrupt child and acting as moral leaders responsible for teaching obedience, discipline, and virtue.3

During the 18th century, childhood and motherhood evolved alongside a myriad of political, religious, and philosophical changes. Political thought began to lean heavily on Enlightenment theory, which gradually began to permeate American culture and viewed the natural world as understandable and predictable. This translated to cultural thought and parents began to see children not as naturally corrupt, but rather born in a neutral (or even good!) state that could be anticipated.4 This shift emphasized the natural flexibility of the child, who required a gentle hand of education and nurture to lead them into adulthood.

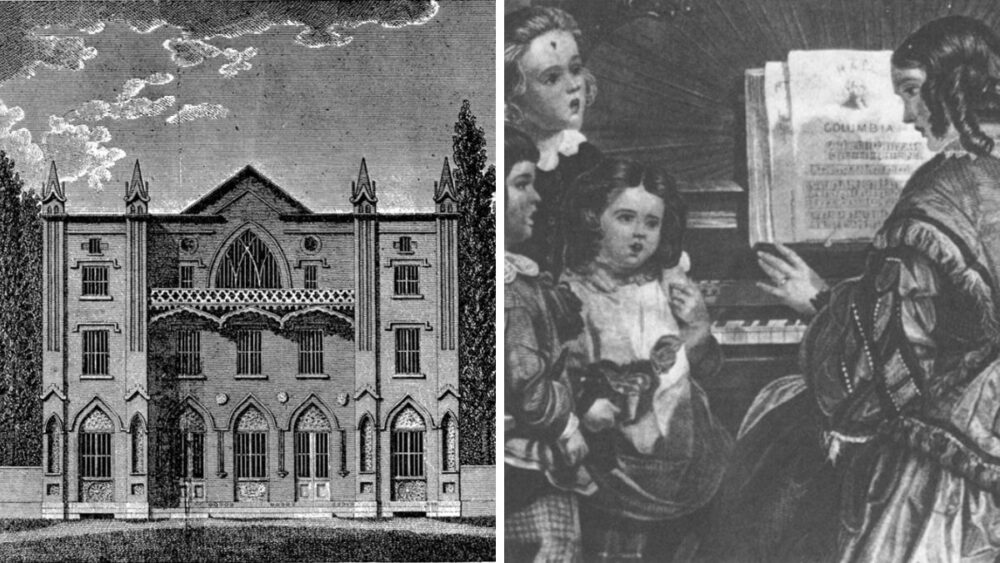

Enlightenment theory viewed women as intrinsically gentle, and mothers began to hold the responsibility of fostering the intellectual and spiritual development of their children.5 Developing religious groups such as Evangelicals contributed to the evolution of motherhood as well, emphasizing women’s natural holiness.6 This was exacerbated in the wake of the Revolutionary War when political leaders put pressure on children to carry forward the country and foster the virtue of the new nation. Women began to occupy a large responsibility as the primary teachers of virtue, while in the colonial period, their roles had primarily been caring for their husband and reproductive labor. These changing cultural perspectives had a circular effect: as mothers became more important in the family, young girls began to receive more standardized education to prepare them for the role of educator and moral instructor in their families.7By the early 19th century, the ideal of womanhood was intrinsically connected to motherhood, a vocation which began to center around virtues of love, gentleness, care, and moral rigor.

Enlightenment theory viewed women as intrinsically gentle, and mothers began to hold the responsibility of fostering the intellectual and spiritual development of their children.5 Developing religious groups such as Evangelicals contributed to the evolution of motherhood as well, emphasizing women’s natural holiness.6 This was exacerbated in the wake of the Revolutionary War when political leaders put pressure on children to carry forward the country and foster the virtue of the new nation. Women began to occupy a large responsibility as the primary teachers of virtue, while in the colonial period, their roles had primarily been caring for their husband and reproductive labor. These changing cultural perspectives had a circular effect: as mothers became more important in the family, young girls began to receive more standardized education to prepare them for the role of educator and moral instructor in their families.7By the early 19th century, the ideal of womanhood was intrinsically connected to motherhood, a vocation which began to center around virtues of love, gentleness, care, and moral rigor.

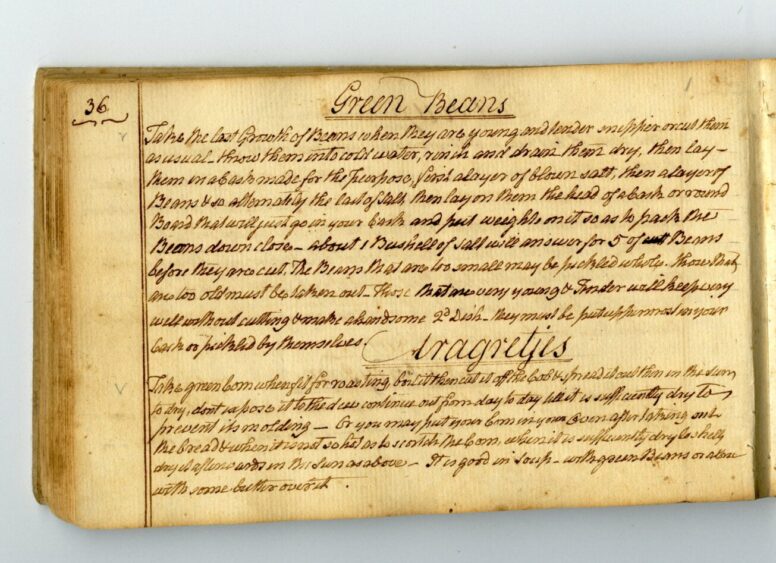

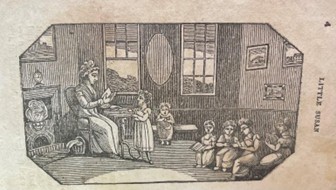

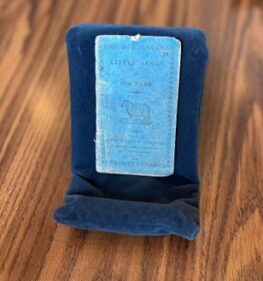

Waking up on a sunny day in the 1830s, a young, upper-class white girl might have begun her day by throwing back her covers and grabbing a book from her bookcase. At this age, perhaps she picked up the 1829, “Little Susan and Her Lamb,” published and sold in New York, and written for, “…Little girls… who like learning better than play, and little books more than to spend their money on cakes…”8 The images in this book display a mother reading to her small children in the home, demonstrating her mastery over domestic life and her role as the leader of her offspring’s education. In the narrative of the book, the author describes Susan as holding the qualities most desired in mothers, showing little Susan as nurturing, caring, and gentle. The story shows Susan adopting a small lamb and rescuing it from slaughter, then caring for the lamb, placing Susan’s maternal characteristics in the forefront. Her mother plays a role as a comforting character in the story as well as a supportive, caring woman who conducts domestic chores such as spinning wool and feeding her children. A young girl consuming books like these might have internalized this message and based her life goals around this concept of womanhood.

Waking up on a sunny day in the 1830s, a young, upper-class white girl might have begun her day by throwing back her covers and grabbing a book from her bookcase. At this age, perhaps she picked up the 1829, “Little Susan and Her Lamb,” published and sold in New York, and written for, “…Little girls… who like learning better than play, and little books more than to spend their money on cakes…”8 The images in this book display a mother reading to her small children in the home, demonstrating her mastery over domestic life and her role as the leader of her offspring’s education. In the narrative of the book, the author describes Susan as holding the qualities most desired in mothers, showing little Susan as nurturing, caring, and gentle. The story shows Susan adopting a small lamb and rescuing it from slaughter, then caring for the lamb, placing Susan’s maternal characteristics in the forefront. Her mother plays a role as a comforting character in the story as well as a supportive, caring woman who conducts domestic chores such as spinning wool and feeding her children. A young girl consuming books like these might have internalized this message and based her life goals around this concept of womanhood.

The changing notions of motherhood in the 18th and 19th centuries did not apply to all women equally. Society excluded women of minority races and lower classes from this model of motherhood, with images of sentimental motherhood depicting only white, middle- or upper-class mothers.9 Both the idea of motherhood and the realities of childbearing looked quite different for poor or minority groups. White, upper-class women were given the time to stay at home and educate their children, while women of lower classes or minority races often worked outside of the home. By the mid-19th century, white upper-class women would often hire help to assist in the more labor intensive aspects of child rearing, while they focused on the intellectual and moral duties.10 Enslaved mothers and free Black mothers in both the North and the South faced the trauma of separation from their children and the dangerous stereotypes society created about their parenting abilities.11 Despite these difficulties, black mothers fought for parental rights over their children and the freedom to mother in their own right.12 Reading these miniature storybooks and thinking about these nuances made me consider how motherhood is socially constructed today and what biases and unrealistic standards still remain.

Shayna Murphy was the 2024 Margaretta (Happy) Rockefeller Research Fellow. She holds a B.A. in History and Anthropology from SUNY New Paltz and is currently a doctoral student at Stony Brook University where her research focuses on enslaved families in New York during the time of gradual emancipation. Her employment and volunteer work at Hudson Valley museums (Historic Huguenot Street, Haviland-Heidgerd Historical Collection, the Reher Center, and the Eleanor Roosevelt Center) has given her experience in public history and a motivation to uncover the lives of women from this area.

1 Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Hymns in Prose for Children, by the Author of Lessons for Children, 1814. Historic Hudson Valley, Collections of the Library.

2 Barbauld, Hymns in Prose for Children.

3 Karin Calvert, “Children in the House.” The Material Culture of Early Childhood 1600-1900 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992).

4 Steven Mintz, Huck’s Raft: A History of American Childhood (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2004), 59.

5 Nora Doyle, Maternal bodies: Redefining motherhood in Early America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

6 Ruth Bloch, “American Feminine Ideals in Transition: The Rise of the Moral Mother, 1785-1815.” Feminist Studies 4, no. 2 (1978): 101–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177453.

7 Catherine M. Scholten. Childbearing in American Society, 1650–1850 (New York: New York University Press, 1985).

8 Little Susan and Her Lamb, 1829, Historic Hudson Valley, Collections of the Library.

9 Nora Doyle, Maternal bodies: Redefining motherhood in early America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

10 Deborah Gorman, The Victorian Girl and the Feminine Ideal (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982).

11 Crystal Webster, Beyond the boundaries of childhood: African American children in the Antebellum North (Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 2021).

12 Crystal Webster, Beyond the boundaries of childhood, 114-141.