Dickens and Irving: A Tale of Two Christmas Tales

Washington Irving’s most memorable tales are indelibly associated with the American holiday of Halloween: who can deny the spooky power of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” or even “Rip Van Winkle,” with its ghostly Henry Hudson and crew? But few fans of these stories know that they first appeared alongside a collection of sketches that would have a profound impact on our concept of an English Christmas. Yes, an English Christmas!

Irving described the customs, decorations, and foods of a rural Christmas in Yorkshire in a series of accounts that appeared in The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, published in 1819-1820, the same book that contains his tales of Rip and Ichabod.

Crayon, his narrator, spends most of The Sketchbook observing life in London and around the English countryside, and while elsewhere in the book he takes a jaundiced view of all things British, in the Christmas stories he is wholehearted in his praise for the holiday he spent at the estate known as Bracebridge Hall.

In his enthusiasm, Crayon depicts Squire Bracebridge, a country gentleman who “prides himself upon keeping up something of old English hospitality,” and the Tudor-style festivities he oversees at Bracebridge Hall, with a precision that is downright anthropological.

“Here were kept up the old games,” Crayon rhapsodized, “of hoodman blind, shoe the wild mare, hot cockles, steal the white loaf, Bob apple, and snap dragon: the Yule clog [sic], and the Christmas candle, were regularly burnt, and the misletoe, with its white berries, hung up, to the imminent peril of all the pretty housemaids.”

Nor did the Bracebridge Hall pheasant pie (ornamented with peacock tail feathers) and wassail bowl, “highly spiced and sweetened, with roasted apples bobbing about the surface” go undocumented (or unconsumed).

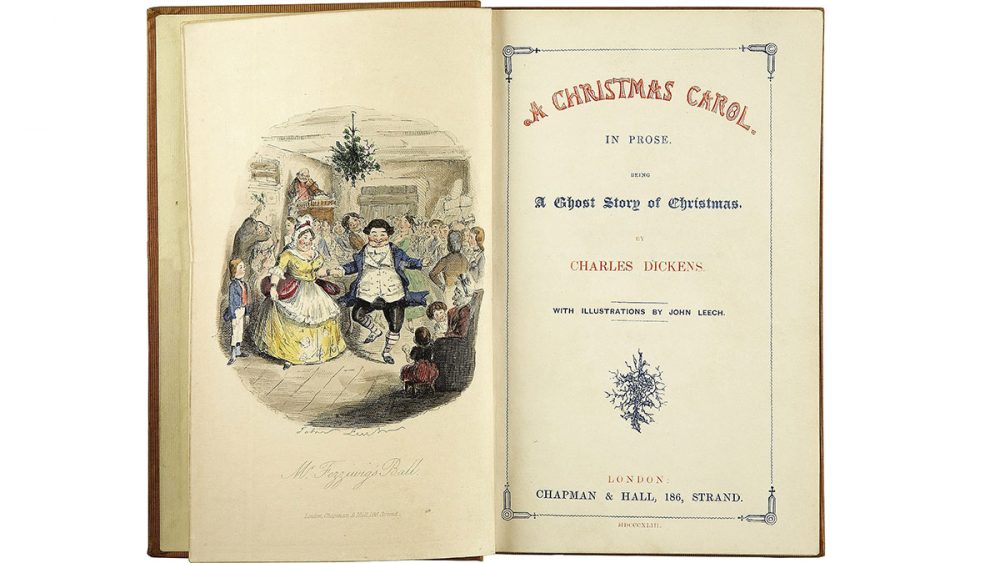

If all this description sounds like pointless digression, it didn’t strike one of Irving’s foremost admirers that way: Charles Dickens. Dickens was just eight years old when The Sketchbook was published, but twenty years later he would send Irving a letter expressing his admiration for the Bracebridge stories.

“I wish to travel with you… down to Bracebridge Hall,” he wrote to Irving in 1841. Such a trip was never made, but that didn’t stop Dickens from using Irving’s holiday tales as his inspiration: A Christmas Carol was published just two years later, and brought the young English author lasting fame. A careful reader doesn’t need to know about Irving’s celebrity fan mail to see the influence that Crayon’s account had on the more famous, Dickensian Christmas. In Irving’s early sketch, readers can find the foundations of Dickens’ beloved scene from “Christmas Past,” a scene that authors, artists, filmmakers and merchandisers have since seized upon as the quintessence of the English holiday. If we look harder, we can also find the ancestors of Dickens’ jolly Fezziwig family in Squire Bracebridge and his hospitable clan.

“How easy is it for one benevolent being to diffuse pleasure around him; and how truly is a kind heart a fountain of gladness, making everything in its vicinity to freshen into smiles,” Crayon wrote of his Christmas host. The same can be said of Irving: even the stories we thought we didn’t know “diffuse pleasure” around us, and “freshen” our understanding and our enjoyment of the ones we thought we knew by heart.

Elizabeth L. Bradley is the editor of the new Penguin Classics edition of Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Other Stories, as well as Irving’s A History of New York. She is the author of Knickerbocker: The Myth Behind New York and Historic Hudson Valley’s Senior Director of Programs and Engagement.