Silver and Sentiment: WHI Fellow Cynthia Smith on Charlotte Irving’s Bouquet Holder

Lately, decluttering has become a popular cultural trend with tidying experts such as Marie Kondo advocating reorganization as a means to “spark joy.” Although living in a clean home can bring contentment, those who declutter are often surprised to find that the act of choosing what to keep becomes a reflective rediscovery of their own identities – their possessions tell them what they’ve valued and what they continue to hope for in the future. All objects have a story, and for the historic houses in the Hudson Valley, it is the possessions of the people who lived in these homes that are at the heart of the narratives we tell about them.

Washington Irving’s home, “Sunnyside,” tells a particularly rich story about the bonds between the Irving family members. When Washington Irving’s older brother, Ebenezer Irving, experienced financial difficulty after the Panic of 1837, Washington invited his brother, five daughters, and youngest son to live at Sunnyside. Within the Historic Hudson Valley Collections, there is a bouquet holder that belonged to Charlotte Irving, Ebenezer’s youngest daughter whom everyone affectionately called “Charlie.” Designed with flowers, birds, thistles, and leaves, the holder was given to her in 1847 by her husband, William R. Grinnell, when they were married. Interestingly, one of William’s uncles had a summer home next door to Sunnyside. Where Charlotte actually met her husband is still a mystery, however, the two would have had many opportunities to meet either in Tarrytown or New York City as the Grinnell and Irving families were frequently in the same social circles. The holder itself was used as an accessory for dances. The side pin would hold the bouquet of flowers in place within the cone-shaped holder, and the ring allowed Charlotte to wear the bouquet while dancing.

While the bouquet holder itself represents the love the newly wed couple shared, the purpose of the object as an accessory for dances also relates to the bond between Charlotte and her well-known literary uncle. Dances were a topic of interest for Charlotte, her sisters, and their uncle, whom they fondly called “Uncle Wash” or “the Illustrious One.” When Washington Irving went abroad to Spain from 1842 to 1846 as an ambassador for America, he frequently wrote to his nieces to ensure their well-being and happiness at Sunnyside. In an especially endearing letter to Charlie dated June 13, 1844, Uncle Wash excitedly refers to a dance hosted by Charlotte’s cousin, Julia, that his nieces had attended. Washington guesses that Charlie’s gown was made of “white taclatan” and jokes “don’t tell [your sisters] . . . what I mean for your private ear that however fine they may have appeared, I rather think the taclatan [tarlatan] must have carried the day.” He thanks her for “representing little Sunnyside so well” at the dance and encourages her to write “all about your summer gaieties; whether you have any pic-nics of old, any musical parties – any dances to the piano-may you have merry times and frequent occasion to figure in the taclatan.”

Uncle Wash’s jokes and interest in Charlotte’s everyday affairs shows the great concern he had for the happiness of his nieces. Having lost their family fortune and home, Washington specifically wanted to make sure that his family felt safe and comfortable at Sunnyside. Although we do not have Charlie’s replies, the content from Irving’s epistle also indicates Charlie’s care for her uncle who was homesick and longing for news from home. Charlie’s letters most likely cheered Irving a good deal, especially as he suffered from health issues during his time abroad.

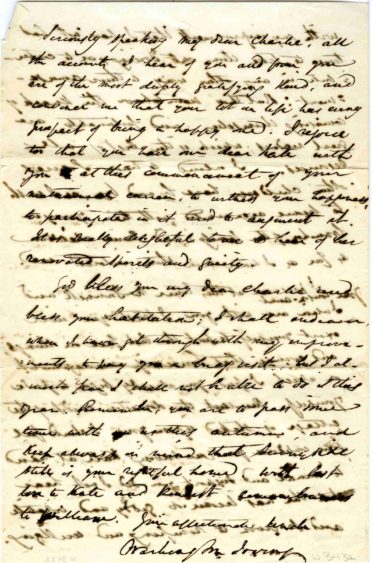

When Charlie married in 1847, she sent her uncle a letter detailing news about her new life. Uncle Wash, who was now back at Sunnyside, wrote her a response on August 13th expressing good wishes: “[M]y own dear Charlie, all the accounts I hear of you and from you are of the most deeply gratifying kind, and convince me that your lot in life has every prospect of being a happy one. God bless you my dear Charlie and bless your habitation.”

In addition to sending Charlie his congratulations, Irving also recognized that marriage oftentimes placed women in vulnerable circumstances. For instance, in the early nineteenth century married women gave up their legal rights to their husbands through the law of coverture, including property rights, and the legal power to sign contracts. Irving recognized that if unforeseen circumstances occurred – if William passed away at a young age – Charlotte would be left in dire circumstances. To reassure his niece that she always has the support of the Irving family, he concludes the letter with this heartfelt sentiment: “Always keep in mind that Sunnyside is your rightful home.” Today, the belongings of the Irving nieces have a significant presence in Sunnyside, reminding us of their stories and the close bonds that they shared as members of the Irving family.

Interested in learning more about our Women’s History Institute Summer Research Fellowship, including information on how to apply? Click here.