The Crane Monument

![SEE DIVORCE DOC[1]4](https://hudsonvalley.org/wp-content/uploads/SEE_DIVORCE_DOC14-870x489.jpg)

By Lucy Brewster, Vassar College

Women’s History Institute Fellow, Historic Hudson Valley, 2021

For visitors walking through the Sleepy Hollow cemetery, one memorial stands out: a tall stone monument with names engraved on each side, standing high above surrounding tombstones. While this grave site is far from the most famous in the cemetery that houses Washington Irving, it is a clue to unraveling a remarkable story—a testament to a mother’s love, painful loss, and fortitude passed down through generations of women.

The monument Gertrude Beekman (1830-1913) erected for her child Annie Crane (1845-1900), Annie’s husband James Crane, and their daughter Gertrude “Gertrie” Crane (1867-1875) symbolizes the deep love Gertrude Beekman had for her children and the pain that surely came from outliving all of them.

Gertrude’s investment in maintaining the graves in the plot—including those of her daughters Hannah and Josephine who died as children—shows her resilience through great loss. Yet her strong bond with her daughter Annie stands out, as clearly as the Crane Memorial that is in tribute to her.

In a world in which many opportunities were closed to even privileged women, Gertrude and Annie were remarkably independent. Gertrude owned property, negotiated her own business dealings and financial affairs, and kept boarders in her home. Annie, too, gained financial independence and personal agency following her first husband’s death. She traveled frequently to New York City and attended typography school, seeking skills that would make her employable.

Gertrude Beekman was born into one of the wealthiest families in 19th-century New York. She was raised in Tarrytown by parents Eliza Adams Beekman (1784- 1845) and Gerard Beekman (1774 – 1837). Gertrude’s paternal grandmother Cornelia Beekman (1753- 1847) grew up at Van Cortlandt Manor. The feisty daughter of Pierre and Joanna Van Cortlandt, Cornelia stood up to British soldiers during the Revolutionary War and recounted the experience for her parents in a letter.[1]

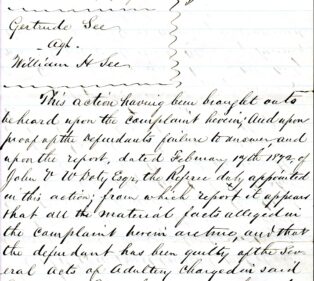

Gertrude was married in Tarrytown at the age of fourteen to William H. See, and bore her daughter Annie barely a year after the marriage. Later, Gertrude divorced William on charges of adultery, first suing for a legal separation 1869 before being granted a complete divorce in New York State Supreme Court in 1872.[2] Documents related to the divorce held in Historic Hudson Valley’s library served as an entry point into my research this summer. Many more avenues of investigation opened up as I discovered more about Gertrude’s life, both at HHV and at other institutions, such as the New York Historical Society, the Grolier Club, The Historical Society of Sleepy Hollow and Tarrytown, and the Westchester County Archives.

Divorce was rare and held deep social and religious stigma in late 19th-century America. Divorces were most often initiated by women who, after being deserted or abused by their husbands, depended on the courts to grant them alimony. While divorce presented women with an opportunity to gain some financial and legal independence, the procedure often favored men and was not an option for many women who did not have access to lawyers or other resources to navigate a legal system dominated by men. In New York in the 1870s, the only grounds for which divorces were granted was adultery.[3]

While Gertrude was successful in suing See for divorce and proving his alleged adultery, she faced scrutiny in the press. Even decades after the divorce, the New York Evening World called the divorce “bogus” in 1890.[4] During the court proceedings, Gertrude was granted custody of her and William’s only surviving minor child, Abel Stewart See.

Gertrude maintained her fiery spirit throughout her entire life, defying social expectations and raising the eyebrows of many of her contemporaries. In articles from 1880-1890, the Tarrytown Argus newspaper records show she was an object of curiosity and fascination from the press as she was embroiled in numerous scandals throughout her lifetime. From initiating the complete divorce from her husband, to marrying her first cousin shortly before he died, to engaging in a long court battle about the will of her first cousin, Gertrude was unafraid of conflict and was a lightning rod for public interest.

Gertrude and Annie, only fifteen years apart in age, remained close well into Annie’s adulthood. Annie lived with her mother after the deaths of her first husband, James Crane and of her daughter, Gertie. Annie still resided with her mother in Tarrytown even after marrying her second husband James Varick. One can imagine that they bonded over losing young children; Annie’s daughter Gertie died at eight years old. “I had just lost all I had in the world, my only child,” Annie said of her daughter’s death during the legal battle over Stephen F. Beekman’s will in court.[5]

Annie’s sworn testimony during the court case over Stephen Beekman’s will is perhaps the best demonstration of the strength of Annie and Gertrude’s relationship. The crux of the case was the question of whether Gertrude and Annie manipulated Stephen into writing a will that favored Gertrude. Stephen was Gertrude’s first cousin and boarded with her in the last years of his life after leaving his mistress and being estranged from his wife. In 1881, less than a year before his death, he wrote a will giving Gertrude his entire estate worth an estimated $20,000 to $25,000. His estranged wife, Georgianna L Beekman, and his mistress, Maria Emily See,[6] both filed legal objections to the will, claiming Gertrude manipulated Stephen. “A curious will contest was begun yesterday in the Westchester County Surrogate’s Court at While Plains… Gertrude Beekman and her daughter were present together in the courtroom,” as The New York Times described of the legal battle.[7]

During the legal dispute, Annie defended herself and her mother against accusations that they conspired to take advantage of Stephen. “I never talked with Mr. Beekman about his property affairs, never mentioned his will to him in my life. I never did anything to persuade him to leave New York and come to Tarrytown,” Annie explained. “I know [my mother] did not,” she responded to the lawyer’s questioning.[8] In 1886, the court finally affirmed the will and ruled on Gertrude’s side.

Annie died in 1900 of phthisis and she did not leave a will. A surrogate of the court left her possessions and estate to her closest living relative, her mother. “And we do by these presents depute, constitute and appoint you the said Gertrude Beekman administratrix of all and singular the goods, chattels, and credits which were of the said Annie E. Crane deceased,” the document read.[9]

Despite two marriages and multiple children, both Annie and Gertrude died without direct heirs. Gertrude’s other daughters, Josephine and Hannah, died as young children. Abel Stewart died a few years before Annie in 1891 of “consumption”, which we now know to be tuberculosis.

While outliving all of her children, Gertrude still paid tribute to her children’s memory in the will she wrote in 1913, a year before she died. “I give and bequeath to the trustees of the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery the sum of $1,000 in trust.” Gertrude requested that the plot, known as Beekman Reserve, be maintained with flowers and plants.[10]

Gertrude’s action to ensure the maintenance of her children’s graves after her own death is another example of the independence she exerted throughout her life. While many families may have shared a fund among family members or a patriarch would have been responsible for funding the maintenance of their family burial plot, this was a final and sacred rite Gertrude took on by herself.

Although the plot in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery where the Crane Memorial stands houses the stones of all of Gertrude’s children, Gertrude was buried in the Beekman family crypt. However, a threshold stone engraved with Gertrude’s name stands a few feet in front of the Crane memorial. Perhaps a descendant saw it fitting that a monument to Gertrude lie near her children.

The plot remains a testament to the deep bonds families hold through generations and the many ways in which people build resilience through great loss.

[1] Jacob Judd, ed. Correspondence of the Van Cortlandt Family of Van Cortlandt Manor, 1748-1800. (Tarrytown: Sleepy Hollow Restorations, 1977): 243-246.

[2] Gertrude Beekman’s Divorce Papers, 1869-1871. Historic Hudson Valley Library. Manuscript Collection.

[3] Norma Basch, Framing American Divorce: From the Revolutionary Generation to the Victorians. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

[4] New York Evening World, November 18,1890.

[5] New York Court of Appeals Records and Briefs: In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of Stephen F. Beekman, Deceased. 43. Vol. 43, 1886, 258.

[6] See was a common name in both Tarrytown and New York City during the 19th century. During the court case there is no familial relationship identified between Maria Emily See and William See.

[7] “Three Wills and Three Women; Contest over the Estate of the Late Stephen F. Beekman.” The New York Times, October 4,1882.

[8] New York Court of Appeals, 261.

[9] Historic Hudson Valley Library. Manuscript Collection, B 2122.

[10] Gertrude Beekman, Last Will and Testament. Westchester County Archives, 1914 (A-0154(176)F, folder 1).