Using Receipts to Trace Families, Cultures

By Sara Evenson, PhD candidate, SUNY Albany

Women’s History Institute Fellow, Historic Hudson Valley, 2020

This has been a summer like none other in my life. The world around us all has been filled with uncertainty and that uncertainty has touched every aspect of our lives. Questions of health, safety, food security, and physical contact—the very basic building blocks of our human existence—have been central to dialogues for the past six months. Day to day, we have no certainty. Except, of course, the certainty that comes from studying the past. The certainty I have found as I walk into the archives at Historic Hudson Valley each week, and begin my methodical searching for tidbits that help to shed light on kitchens in the eighteenth century. After all, that’s why I came here—to study kitchens. Funny, though, how the uncertainty of life can lead you to strange places, just as fortuitous discoveries in the archives can lead you to entirely new places. Funny that I have found a research rhythm and a routine for the summer in, at least partially, the family of a man best known for his publications on medical jurisprudence. And especially funny that I have found his story, and his family’s story, through the very unexpected entry point of an old Dutch recipe.

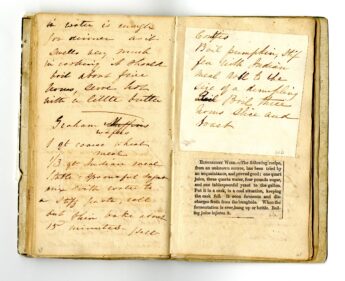

Sorting through the collection of historic cookery books in the HHV collection this summer, I found myself particularly taken by two: The Beck Market Book (1820s-30s) and the Van Cortlandt Receipts (1865). I’m usually more interested in earlier receipt books, especially those from the eighteenth century. But as I read through these two books I was struck by some interesting similarities, and by some truly unique recipes. I needed to know more.

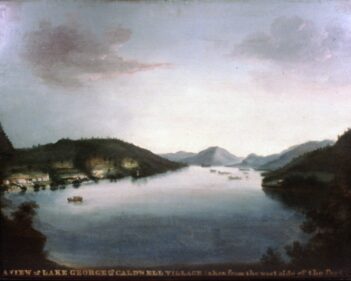

The common element between these two books is Catherine Beck Van Cortlandt. In 1836, Catherine Beck and Pierre Van Cortlandt III were married in Albany.[1] The couple settled at Van Cortlandt Manor in Croton-on-Hudson, the rural 17th-century home of the Van Cortlandt Family.[2] The union of Pierre and Catherine brought together two uniquely New York lineages. The Beck and Romeyn (Catherine’s mother’s maiden name) lines had been deeply invested in the Albany and Schenectady area for generations, staking their futures in the Upper Hudson Valley. Through this lineage, Catherine possessed Dutch and English ancestry, in addition to Irish blood from her grandfather James Caldwell.[3] It is through Caldwell that Catherine also had direct ties to the Lake George region, and by association to the great waterways north from Albany into Canada. By marrying Pierre Van Cortlandt, the grandson of politically-connected landowners Pierre and Joanna Van Cortlandt, she forged connections with a prominent new world Dutch family of the Lower Hudson. In many ways, this one woman encapsulates the essence of New York during the late 18th and early 19th centuries: a polyglot of cultures forging connections along the major travel routes of the era. This is the woman who perhaps unknowingly tied together the Upper and Lower Hudson Valley with something so simple as a few recipes, and so seamlessly blended Dutch and English ancestry with American tastes as to create a food experience that uniquely displayed New York terroir.

The Beck Market Book held by HHV is dated to the 1820s and 1830s. It is a small volume filled with handwritten recipes, interspersed with printed recipes, recipes and handy hints that were published in newspapers or magazines, clipped, and then pasted into the book. There are three particularly interesting recipes in this book that demonstrate just how complicated early 19th-century New York was. The first two are Lake George Fruit Cake, and Lake George Sugar Cake. It isn’t unusual for 18th– and 19th-century recipes to be named for a geographic region or township. This book also includes a recipe for New York Cup Cake, but these two Lake George recipes puzzled me. There is nothing about them that seems particularly regional, and especially not specific to the Lake George area, far north of both Croton-on-Hudson and Albany. The explanation became apparent to me with a little digging: Catherine’s grandfather, James Caldwell, owned substantial property near Lake George. In fact, the area now known as Lake George Village once all belonged to the Caldwells, and was even named Caldwell in recognition of the family.[4] The Caldwell family lived mainly in Albany where James’ business interests were, but kept their estate near Lake George and frequently stayed there during the summer months.[5] The Beck family’s Lake George recipes were from a direct geographical connection to the region. Perhaps the family enjoyed these baked goods as special treats while they summered on the southern shores of Lake George. It’s certainly easy to imagine the family taking the sweet, buttery Sugar Cakes on lake outings with their family.

Catherine’s Hudson Valley connections are just as evident in this cookery book, and with these sugar cakes. While Lake George itself is not connected to the Hudson River, the township of Caldwell stretched from the lake northwest toward the Hudson River.[6] In many ways these areas are culturally tied together by the generations of people who traveled either up or down the spine of New York from Canada to New York City along the great lakes and river systems that geographically connect these two vital areas. While not directly connected to one another by water, Lake George and the Hudson River are most certainly geographically connected as a major north-south travel network that predated the canal era. Intentionally or otherwise, the Becks and their Lake George recipes are just as steeped in the culture of the Hudson River Valley as the third recipe recipe that caught my eye: contjes.

According to the Beck Market Book, contjes are made in the following way: “Boil pumpkin, stiffen with Indian meal till to the size of a dumpling. Boil three hours, slice and toast.” Contjes are essentially a pumpkin cornmeal dumpling that, after being boiled, is sliced and toasted. On its surface this sounds like a delightful autumnal dish, almost like a pumpkiny corn-toastie that modern readers may be familiar with. More investigation shows just how significant this recipe is. The combination of pumpkin and cornmeal make it a uniquely hybrid culinary creation. Both maize and pumpkins were native to North America and therefore unknown to the rest of the world until globalized trading networks began after 1492. However, the tradition of boiling dumplings was common throughout Europe. What makes these contjes particularly interesting, though, are two things: their method of preparation and their very name themselves, and how these two things make contjes a unique culinary item.

Writing from Montreal in September of 1749, the noted explorer and naturalist Peter Kalm took the time to mention how different people prepare and consume pumpkins. “Pumpions,” he wrote, “are prepared for eating in various ways. The Indians boil them whole, or roast them in ashes, and eat them then, or go to sell them thus prepared in the towns, and they have, indeed, a very fine flavour, when roasted.”[7] The “French and English,” he said, however tended to slice the pumpkins before roasting and would then sweeten them with sugar.[8] He also noted that “They” will often slice and boil the pumpkin in water, after which It is strained and mashed. The mashed pumpkin would then be heated with milk and mixed with maize flour and then made into cakes.[9] Kalm’s reference to “they” can mean anyone ranging from Native Americans to settlers of French or English heritage living in the Americas—those individuals he mentions previously. It is important to note, however, that he makes no connection between this dish and any Dutch group or individual. Kalm makes a point of associating specific dishes, traits, and cultural styles with different ethnic groups throughout his journals, so this is unlikely to be an unintentional omission.[10] The Becks, or whomever they learned this recipe from, intentionally used a Dutch word to describe a dish that their European ancestors had likely not made or ever eaten, and which had no distinct ties to Dutch culture in the Americas. Why they did this remains a mystery to me, though I have a speculation: this particular recipe requires that you first boil the pumpkin and cornmeal into a dumpling, and then fry it before eating. Kalm’s observation didn’t specify if the “cakes” he noted were baked or fried, so we cannot be certain of how they were prepared. However, the Dutch word kaantjes translates to “cracklings,” or little fried things. It seems likely that the Becks or the originator of this recipe took a firmly new world dish and named it after something they were familiar with. The act of frying these slices of dumpling became their name, the phonetical contjes of the Beck Market Book.

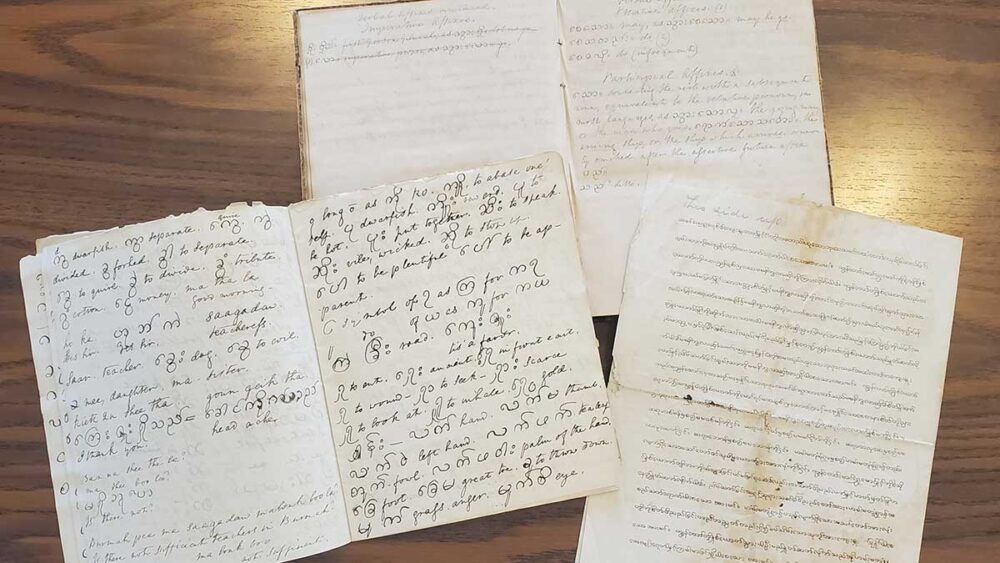

This is not where we leave the contjes, though. In a later 19th-century collection of Van Cortlandt recipes there is a letter tucked in amidst the handwritten and clipped recipes. It opens by saying: “I feel too unwell to write, but will soon. Love to all your [illegible]. C.T. Beck.”[11] This sheet includes a list of old New York Dutch recipes such as olicookes (small pieces of fried dough) and pufferts (boiled or steamed pudding) and, perhaps not surprisingly, cantjes. Despite the slightly altered spelling, the recipe for cantjes is nearly identical to the earlier Beck Market Book recipe for contjes, including the critical steps of first boiling and then frying the sliced dumpling.[12] The C.T. Beck who authored this note was likely Catherine Theresa Romeyn Beck, paternal grandmother to Catherine Beck Van Cortlandt.[13] After Catherine’s mother died, she relied heavily on her grandmother. It seems likely that grandmother wrote this note of old family recipes for her married granddaughter to include in her own recipe collection. Contjes or any similar recipe does not appear in any eighteenth century recipe books attributed to the Van Cortlandt family, which implies that this particular dish was introduced to the family by the Beck branch.

And so despite the uncertain times we’re living in and the anxiety many of us, especially students and educators, have about fall approaching, I also remain excited. I have a bag of cornmeal from the Ganondagan State Historic Site, and pumpkin season is almost here. This fall I will become a part of the Beck and Van Cortlandt story when I mix the two together, and then fry them on a griddle to prepare contjes. I may not fully understand the origin of these little fried cakes, and I may not fully understand the world around me, but I can find a few moments of connection with women far distant from me as I stir, and pour, and watch the pan sizzle.

[1] Mary L.D. Ferris “Catherine Elizabeth Van Cortlandt,” reprinted from the New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, 1895, Historic Hudson Valley Library, Pamphlet File.

[2] Kate Eagen Johnson, Van Cortlandt Manor. (Tarrytown: Historic Hudson Valley Press, 1997), 7.

[3] Tricia Barbagallo, “James Caldwell: Immigrant Entrepreneur,” 2000, https://exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov/albany/art/art-jctb.html

[4] Ibid.

[5] Regina Berry, “James Caldwell Family Papers,” 2015, http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/msscfa/sc20327.htm

[6] H.P. Smith. “History of the Town of Caldwell,” 1885, http://sites.rootsweb.com/~nywarren/countyhistory/smith/xxxii.htm

[7] Peter Kalm, Travels into North America, Vol. 2, 1772, http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/fullbrowser/collection/aj/id/16887/rv/compoundobject/cpd/16932: 388.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] It is important to note that I have been working with the 1772 London publication of Kalm’s journals. This edition puts Kalm’s discussion of pumpkins firmly in September of 1749 while he was in Montreal. This matches the 1761 Stockholm version, which was published in Kalm’s original Swedish. It is not until a 1937 edition that we find mention of these pumpkin cornmeal pancakes being tied to Dutch inhabitants of the Hudson Valley, or to Albany itself. This 1937 edition and subsequent 1966 Dover publication are subject to what I would consider creative translation; the original Swedish has been translated in such a way as to appeal to 20th century readers and has a distinctly colonial-revival feel to it. Because of these discrepancies, I have decided to rely on the 1772 English and 1761 Swedish versions as authoritative.

[11] Stevenson-Van Cortlandt Receipt Book, V 2443. Historic Hudson Valley Library, Manuscript Collection, Van Cortlandt Family Papers.

[12] Beck Market Book, V 2447. Historic Hudson Valley Library, Manuscript Collections; Van Cortlandt Family Papers.

[13] Ferris, ibid.