Finding Etched Glass Inscriptions in the Window at Van Cortlandt Manor

A Father’s Love for His Daughter Is Etched in Glass

Talking with our loved ones and visiting friends and family is relatively simple now—maybe you drive 30 minutes to the next town over or take the bus just a few stops. Don’t want to leave the house? There’s always the option of sending a quick text or having an hour-long phone call with those you care about. But of course, it hasn’t always been that easy to remain in direct contact. At the turn of the nineteenth century, letter writing was the primary means of communication—and you could of course always visit, but it would have taken quite a bit of time, especially if you chose to arrive by carriage. So, when family and friends did stop by, those moments of unity were highly valued and certainly recorded. Sometimes recorded however, in a slightly different fashion than we might today. Etched in cursive on a single-pane of glass at Van Cortlandt Manor, reads the following inscription:

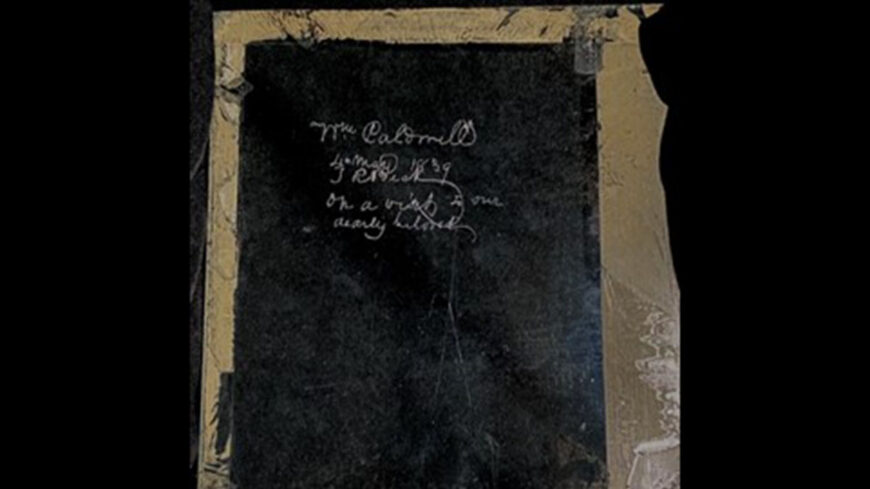

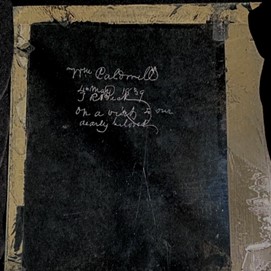

“Wm Caldwell

4 May 1839

T R Beck

On a visit to our dearly beloved” [i]

Window pane etching circa 1839 (VC.96.4)

So, who was T R Beck’s and William Caldwell’s (often abbreviated as ‘Wm’) ‘dearly beloved’?

Pierre Van Cortlandt III and Catherine Elizabeth Van Cortlandt (Beck)

When we think of Van Cortlandt Manor, we think of Pierre Van Cortlandt I and his son, Pierre Van Cortlandt, Jr (or II). With their broad-reaching contributions in the American Revolutionary War and within New York state politics, thinking of the Van Cortlandts’ manor as the place in which New York’s first Lieutenant Governor wrote letters to commanding officers, while overlooking the Croton Bay, makes sense. However once Pierre Van Cortlandt II permanently moved out of the manor to reside in Old Stone (located in Peekskill, New York), Van Cortlandt Manor never sat empty. Temporary inhabited by Philip Van Cortlandt, Uncle to Pierre II, the last iteration of the Van Cortlandts that would find Van Cortlandt Manor to be home, arrived at the manor in the Summer of 1836. [ii] The children of Pierre Van Cortlandt III and Catherine Elizabeth Van Cortlandt will continue to live in the home until it is finally sold outside of the Van Cortlandt family, over a century later in the 1940s.

Pierre Van Cortlandt III, born in 1815 was the only son of Pierre II and Ann Stevenson. [iii] His arrival at the manor was with no one other than his new bride, Catherine Elizabeth Beck. Born in 1818, Catherine was the oldest daughter of Theodric Romeyn Beck, a prominent Albany physician and professor in the field of medical jurisprudence, and Harriet Caldwell, “a woman of fine literary culture and refined nature.” [iv] Unfortunately, Harriet would pass away at the age of 31, when Catherine was only five, leaving Theodric to raise both her and her younger sister, Helen. He was said to have been “devoutly attached” to Harriet and that a good portion of his book Medical Jurisprudence (1825) was written by her bedside. [v] There is no documentation that Theodric ever remarried, and in 1855 he is buried beside Harriet in the Caldwell Family Cemetery in Lake George. His last words, recorded by Catherine herself in a biography she wrote of her father, were “Where is Catherine?” as she had just momentary stepped out of his room. [vi]

Van Cortlandt Manor late-1830s

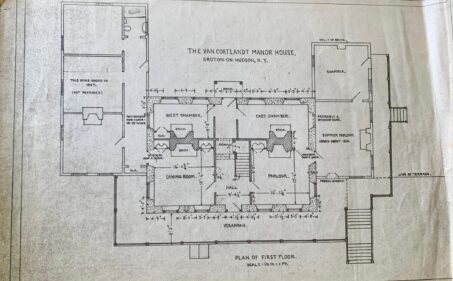

As a father who quite clearly cared deeply for the women in his life, we would expect him to visit Catherine as she settles into life at Van Cortlandt Manor; however, the Van Cortlandt Manor that Catherine and Pierre III moved into in 1836, would have looked quite different than the Van Cortlandt Manor that sits beside the Croton River today. Prior to the couple moving in, a two-story East-wing addition was constructed in approximately 1810—and in the 1840s, Catherine and Pierre III would add a two-story West-wing, along with three dormers on the second-floor. [vii] This means that the currently standing Dutch-colonial structure could actually accommodate quite a few more visitors—and more family members.

First Floor Blueprint of Van Cortlandt Manor circa mid-1940s (VC/House 2018 D)

On May 2, 1838, just shy of celebrating two years at Van Cortlandt Manor, Catharine Theresa Romeyn Van Cortlandt, Catherine and Pierre III’s first child, is born. Her first name is taken from her mother and her middle name(s) taken from her grandfather. [viii] One year and two days later, ‘T R Beck’ marks his visit to Van Cortlandt Manor on a windowpane, in what we can assume was a visit to see not only his oldest daughter, but also to celebrate his first grandchild’s first birthday. The previously mentioned ‘our beloved’ could refer to either Catherine Elizabeth or Catherine Theresa Romeyn. While we don’t know from what room the window pane was taken, we can image Theodric standing in front of a window perhaps overlooking the extensive gardens off of the East-side of the manor, carefully using a ring or pen-knife to record his visit to William Caldwell—William being Harriet Caldwell’s brother, or Catherine Elizabeth’s Uncle. [ix]

Window Etching and Remembering Names

If you were going to visit a family member today, you certainly wouldn’t recount your trip in a brief etched note on a glass pane—you would maybe take a few pictures, but would most likely recall the visit in years to come in a moment of nostalgia. So why, in 1839, would Theodric have thought to mark his name in glass? In a brief 2013 interview for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, Dr. Jim Jordan, a professor of Anthropology and Sociology at Longwood University considers this very same thing—though he is thinking of a few names etched in glass that he found in his own home and at Longwood University. Dr. Jordan notes that this phenomenon is both very common after the Civil War (1860s and onward) and is commonly done by women. [x] Dr. Jordan points to a dormitory where a few women etched their names to stamp their place in time and history—a physical note that they were here. However, Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, American Romantic writer Nathaniel Hawthorne’s wife, would etch several different dates and events into the window panes of Old Manse, the Hawthorne’s home between 1842 – 1845, which pre-dates the Civil War. [xi] While it seems that Theodric’s note might not have been too out of place in regards to the date that it was etched, it does seem remarkable that as a man, he’s etching a glass-pane at all, if we follow the understanding that this was commonly an activity women participated in. While it is difficult to speculate further, we can certainly say that Theodric’s love for Catherine Elizabeth and Catherine Theresa Romeyn is felt over 175 years later.

Notes:

[i] Historic Hudson Valley Collections, VC.96.4, Gift of Mrs. Robert P. Browne

[ii] ‘Catherine Elizabeth Van Cortlandt’ by Mary L. D. Ferris, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. Jul 1895; vol 26, no. 3 (Historic Hudson Valley Collections, SF 920 V26o)

[iii] “The Van Cortlandt Family” by L. Effingham De Forest in The Old New York Families, The Historical Publication Society, New York, 1930

[iv] “T Romeyn Beck” by Catherine Elizabeth Van Cortlandt (Historic Hudson Valley Collections, SF 974.727 BTR 1791 b)

[v] “Euology on the Life and Character of Theodric Romeyn Beck, M.D., LL.D., Delivered before the Medical Society of the State of New York” by Frank Hastings Hamilton, M.D., Albany, 1856

[vi] “T Romeyn Beck” by Catherine Elizabeth Van Cortlandt (Historic Hudson Valley Collections, SF 974.727 BTR 1791 b)

[vii] Historic Hudson Valley Library. Architectural Drawings. The Van Cortlandt Manor House, Plan of the First Floor, c. 1945-1948, VC/House 2018 D, Gift of the Chatfield-Taylor Family

[viii] “The Van Cortlandt Family” by L. Effingham De Forest in The Old New York Families, The Historical Publication Society, New York, 1930

[ix] ‘Catherine Elizabeth Van Cortlandt’ by Mary L. D. Ferris, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. Jul 1895; vol 26, no. 3 (Historic Hudson Valley Collections, SF 920 V26o)

[x] ‘Etching their Names in History’ by Bill Lohmann in Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 18 2013

[xi] Old Manse

Lawrence Lorraine Mullen (they/them/theirs) is a PhD student in the English Department at the University at Buffalo, where their research is currently on 19th-century American Gothic literature. They received their BA from Temple University in English with a minor in Creative Writing and their MFA from Arcadia University in Creative Writing. Mullen was a Women’s History Institute 2022 Summer Research Fellow. Learn more about our Women’s History Institute Fellowships.