The Great American Ghost Story: The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

Autumn in Sleepy Hollow country is a time of traditions: time to visit the Old Dutch Church and the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in their fall foliage, and time to make a pilgrimage to Washington Irving’s Sunnyside, home to the author of what is arguably the most famous American ghost story, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” The ghost in question is, of course, the Headless Horseman, who thundered into the American imagination more than two centuries ago.

But where did the Hudson Valley’s favorite spectral Hessian come from? There has been speculation about the origins of the “Legend” almost as long as Headless has been on the move. Some scholars find the source in Europe: either in Germany, where the Grimm brothers’ “Hans Jagenteufel” (“Hans Huntingdevil”) is condemned to ride headless, or in Ireland where the Dullahan (Irish dubhlachain) strikes blind those who see him and who appears to those about to die. Irving likely heard variations of these stories during the years 1815-1820, during which he traveled through Scotland, England, Spain and Germany, collecting folk tales and ghost stories, a “budget of wonderful stories,” as he wrote to his friend Thomas Storrow, “from every old woman I meet[.]” His mentor, Sir Walter Scott, even penned an English translation of “Der Wilde Jager” (The Wild Huntsman), a German poem that turns on a wicked hunter or “wildgrave” who is himself hounded to hell for his misdeeds.

At the same time, Washington Irving was quite familiar with American tales of the chilling and supernatural, and with the folk history of the region he had visited as a teenager. The “Legend” is full of local haunts and neighborhood ghosts, described to Ichabod Crane by Dutch wives or retired soldiers. Some of these ghosts are as nearly as new to town as Crane himself: Major Andre’s Revolutionary War capture and execution would have been well within the memory of the living residents of Irving’s Sleepy Hollow. Irving also weaves real historic landmarks (such as the Old Dutch Church and Philipsburg Manor, standing in for the home of Crane’s love interest, Katrina Van Tassel) into his fictional tale, leaving readers delightfully unsure of their footing.

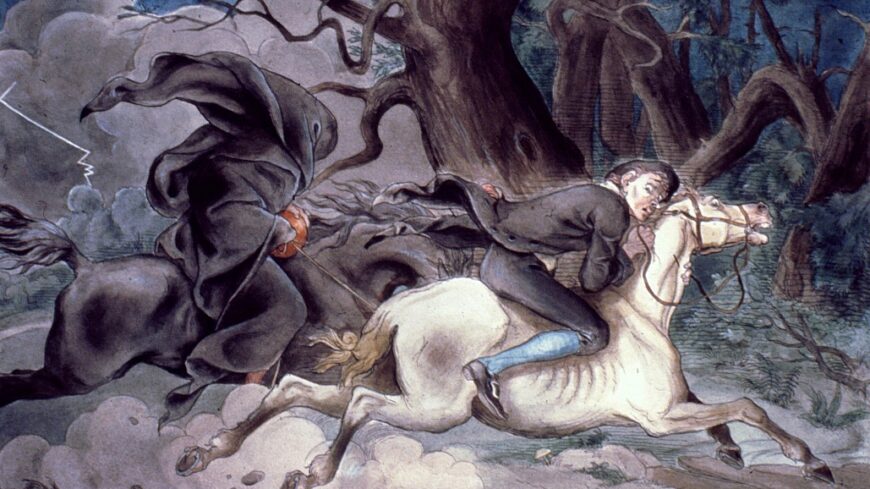

In fact, no actual spooks or spirits are necessary to terrify the Yankee schoolmaster on his ride home; his imagination does that for him. When a silent, caped rider starts following him, it never occurs to Ichabod Crane that his ghostly visitor just might be a prank. And that ambiguity is part of the story’s charm: readers are left to wonder, and to choose the ending they like best. Did Brom know “more about the matter than he chose to tell?” Did Katrina? Was that indeed Ichabod Crane who was later seen presiding as a justice of the Ten Pound Court? Or did the Hessian do away with the Connecticut interloper before he made off with Katrina’s fortune? What really happened in Sleepy Hollow?

Irving took a European horror story and turned it into an American original, and for 200 years now the Legend has had a life of its own. Most visitors to Sunnyside are familiar with the Walt Disney animation of “The Legend,” a 1949 classic narrated by Bing Crosby, with songs by Thurl Ravenscroft of “Grinch” fame. Others know the Tim Burton film made fifty years later, with a memorable Christopher Walken as a particularly vindictive Horseman. Most recently, there’s the avenging ax-wielder of the “Sleepy Hollow” TV series. These adaptations and many more are represented in “Home of the Legend,” a tour and exhibition at Sunnyside that follows the lasting popularity of Irving’s most famous tale and the life of the author who first brought the Headless Horseman to life for American readers, 200 years ago. While you’re there, come see the Horseman for yourself in a new shadow puppet film of the “Legend”– we promise not to spoil the ending for you!