Women’s Fashion in the 19th Century

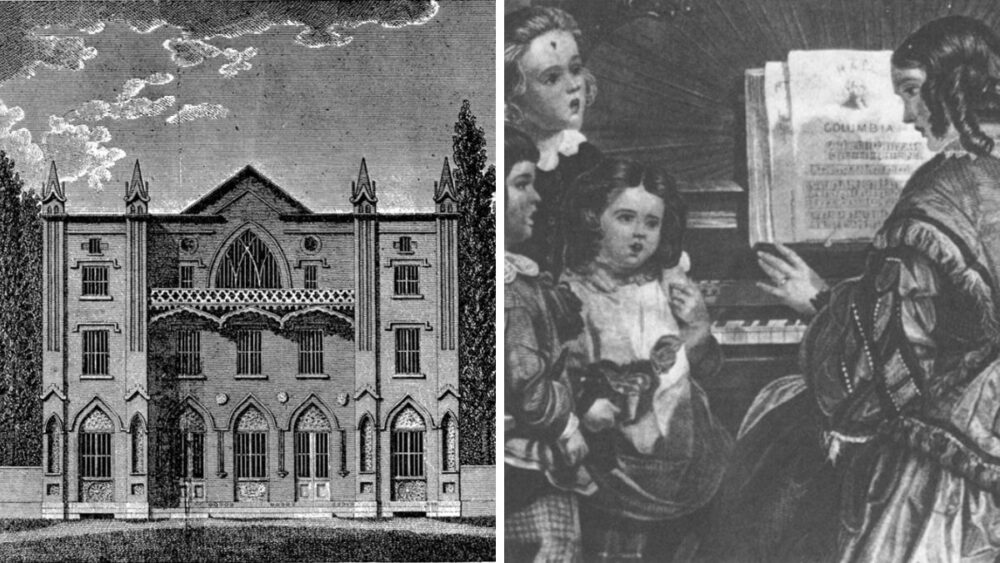

Visitors to Washington Irving’s Sunnyside peek into the bedroom of Sarah and Catherine Irving, but imagine if they could step back in time and open the drawers and closet to reveal the full range of complex garments that made up their wardrobe?

In the 19th-century, all women wore several layers of clothing, though the clothing got more complicated depending on their socioeconomic status. While clothing was determined by the day’s activities, the basic underclothes or “foundational layer” for all outfits — a chemise, drawers, stockings, corset, and petticoats — remained fairly consistent. Working class women wore the same foundational garments as their wealthier counterparts, but theirs may have been made of less expensive materials and with fewer adornments.

Chemises, drawers, and petticoats were made of white cotton or linen. The chemise was the primary layer of clothing all women wore. Since it was the only part of the wardrobe to touch the body directly, this loose-fitting garment absorbed sweat and kept the outer garments (which were much more complicated to launder) clean. This meant that only undergarments needed to be laundered regularly, ensuring that the dresses would last many years while maintaining their color, structural integrity, and embellishments—which could easily be damaged by frequent washing.

Drawers were long, loose-fitting “underpants” that split and overlapped in the middle to allow for easy bathroom access (they could not be pulled down once the corset was on). They covered a woman’s legs to just below the knee and were more for modesty and functional use than style. One had to ensure, after all, that a carelessly lifted hoop skirt would not accidentally reveal anything a lady would not want revealed!

Stockings were typically worn up over the knee. Made of wool, cotton, linen, or silk, they were held up by knitted or woven garters or ribbon tied above or below the knee and could be folded over, or not, according to personal choice. Silk and embroidered stockings were more expensive options. Stockings came in all different colors, although white and black were common choices for average use.

Corsets were basically a support garment for the back and chest, not unlike the sports bra is today. A woman put on her corset before her petticoats to help support the hips, the extra weight added by other clothing layers, and the multiple petticoats worn to achieve the bell shape that was popular in the mid-19th century. They were designed for different purposes, such as ventilated ones for summer, maternity wear, and for physical work. Some men wore corsets as well!

In most cases, corsets were made to fit the owner’s proportions. They were made of a combination of fabrics chosen for strength and fashion, and had channels sewn into them where whalebone, reed, or metal bones would be inserted to reinforce their shape. The corset would go through a period of “seasoning” during which the wearer’s body heat would help mold the corset to them, creating even more of a customized fit.

Many of our negative ideas or misconceptions regarding corsets come from fictional accounts, doctored photos, unrealistic portrayals from fashion plates, Hollywood, or even from surviving garments that we see on display in museums and in archives. It is important to recognize that, more often than not, the garments that survive and end up in museums were considered special and not worn on a daily basis. They often come from the social elite, the fashionistas of the day who could engage in extreme fashion just like today’s celebrities. Maybe not so surprisingly, corsets became a popular subject of debate as the women’s rights movement began.

Depending on the plans for the day, a woman would choose how many petticoats and crinolines she would wear. A petticoat was a simple underskirt, whereas a crinoline was stiffened and more structured. Simple day or work dresses were worn with just petticoats underneath, regardless of social class, because it allowed a woman to move about much more easily. The number of petticoats worn depended on the style of dress; as many as eight starched petticoats could be worn underneath a day dress to achieve the iconic bell shape. At least one of these petticoats would often be a corded petticoat. Like the corset, channels would be sewn into the petticoat and horsehair, cabbage (scrap fabric), or whalebone would be threaded through to make the skirts stand at the proper angle. A final petticoat, called the over-petticoat, would be worn over the corded one to smooth out the look of the skirts.

Early crinoline was stiffened much like the corded petticoat. The cage crinoline was invented in the mid-1800s and was constructed to have a framework made of steel, whalebone, or cane. When worn underneath a dress, the “hoop skirt” would flare out, helping to achieve the illusion of a tiny waist, and an over-petticoat would be placed over the cage to smooth over the ridges.

Finally, on top of the petticoats and the crinolines was the final layer of a woman’s wardrobe: the dress.

Dresses were made in a wide range of fabrics, colors, patterns, and designs. They could either be a single piece or two pieces comprised of a separate skirt and bodice. If a woman was attending a party or fancy ball, she would invest in a more structured and complicated dress, which would certainly be worn with a crinoline. Catherine and Sarah Irving, Washington Irving’s nieces, who along with their widowed father and three younger sisters came to live at Sunnyside in 1840, would have had at least two dresses for social gatherings and day dresses that were worn around the house. Day dresses were also appropriate for teatime and greeting visitors into one’s home.

It might seem odd that women of a middle class household had far fewer dresses than a woman today. Before our current expectations of “fast fashion” and mass manufacturing, clothing was valuable, often handcrafted, unique, and expensive, with so much time and effort put into its display. Although the industrialization of textiles and other household items proliferated in the 19th century, these items were still more valuable than their counterparts today.

There are other ways that 19th-century societal norms play out in clothing. For example, middle class women like the Irving nieces would not have been responsible for washing their own undergarments. Instead, the family hired laundresses for this work. Middle class women also lived under certain expectations of behavior that are different than today. It was considered unseemly for women like the Irvings to exert themselves physically. A popular game from the time was called “Graces,” named for the way that a woman should look while playing. In this game, girls or women tossed a hoop back and forth by using a pair of crossed sticks to throw the hoop. The players were not to raise their arms too high, which would have been inappropriate for a lady.

The period attire worn by our interpreters at Historic Hudson Valley helps convey a broader sense of the time periods for each of our sites. At Sunnyside, guides wear both simple dresses, like those of the servants, as well as the more elaborate hoop skirts that the nieces would have worn on more special occasions. Clothing is one layer of interpretation that tells a much larger story of domestic, social, and even political history. The next time you get dressed, consider—what do our clothing choices say about us today?