Susan of Philipsburg Manor

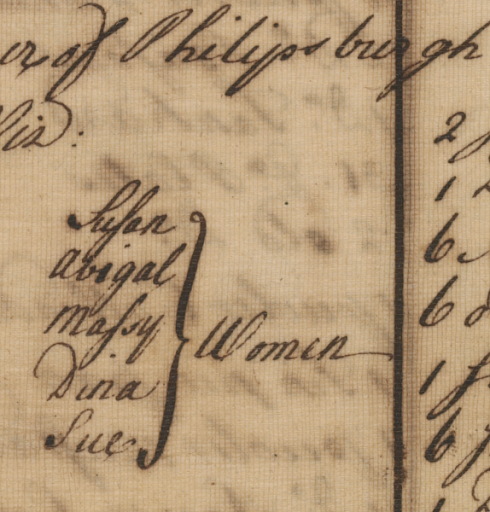

Susan, Abigal, Massy, Dina, and Sue. Five adults enslaved by Adolph Philipse at the Upper Mills in Sleepy Hollow. Who were they? What were their origins? What were their stories?

We know that Philipsburg Manor was a commercial enterprise and that these women operated a farm and a dairy essential to that business of trade. They milked 12 cows, produced butter and packed it into barrels known as firkins that were sold in New York City and shipped to Caribbean plantations. But their stories are more important and complex than just a list of their labors.

We believe that Susan was the most knowledgeable in the task of making butter suitable for the long voyages south. She may also have been responsible for leading the work in the Manor House’s lower kitchen, where she and Abigal, Massy, Dina, and Sue cooked and prepared meals that fed the enslaved individuals.

Susan was also a guiding presence. As possibly the oldest of the women at the Upper Mills, she may have been a link to the earliest generation of Africans who were captured, sold into enslavement, and survived the often fatal “Middle Passage” across the Atlantic Ocean to plantations such as Philipsburg Manor. Her connections with the individuals who first lived at the Upper Mills, and who knew and remembered their African homelands, would have made her a valuable and respected member of the community. Stories, songs, and cultural traditions are pieces of wisdom that would have been shared in the close working spaces of the lower kitchen and dairy, and Susan would have had the knowledge to teach the children.

She was one of several enslaved women of Philipsburg Manor with the same name, which, along with Susanna, is identified as Christian in colonial plantation accounts. Rarely did enslavers refer to enslaved people by the names given by their Igbo, Ashanti, or Kongo families. Occasionally a name can directly or indirectly be traced to a particular culture in Africa, but it was far more common that an enslaver would use Christian or European names instead.

In 1702, the will of Frederick Philipse I, Adolph’s father, lists a “Negroe woman Old Susan” and a “Negroe woman Susan the younger.” This “Susan the younger” could be the same Susan who appeared on a 1750 inventory, just above a woman named Sue. What are the relationships here? Perhaps grandmother-daughter/mother-daughter, or some combination? Though we cannot say for certain, we do know that women gave birth to children at Philipsburg Manor: Dina appears by herself on the inventory and in a document recorded several months later she is listed with an infant child. We also see a similar repetition of names among the men listed on these historical documents. Though families were formed, enslavement offered no guarantee that relatives or social ties would remain intact.

Following Adolph Philipse’s death in 1750, the Upper Mills property was advertised for sale and the inventory included 23 women, men, and children. Susan was listed first among the women, perhaps because of the high value she might fetch at auction. We know from records that nine of the individuals from the Upper Mills were sold and continued to labor for other enslavers.

No known documents survive that tell us what became of Susan, or Sue, following Adolph’s death and breakup of their community. Adolph’s nephew, Frederick Philipse II and subsequent heirs who successively inherited the Upper Mills, also enslaved people for labor at the Manor’s Lower Mills in Yonkers, at warehouses in New York City, and aboard commercial trading vessels on the Hudson River. Susan and Sue may have remained together at one of those locations, but more likely they were forcibly separated and remained enslaved the rest of their lives.

Susan’s story does not end in 1750, or in 1827, the date at which enslavement became illegal in New York. Historic Hudson Valley continues to share what we know of Susan, and of so many other women, men, and children who were captive and brought to Philipsburg Manor, or born into the state’s system of enslavement. Their skill and intense labor produced enormous profit for Adolph Philipse, profit that they themselves would not enjoy or benefit from as enslaved people. Yet their knowledge, shared and created culture, kinships, and relationships expressed their humanity within a small community that constantly sought continuity and survival but liberation as well.