The Swedish Nightingale and Historic Hudson Valley

Annie Muirhead, Historic Hudson Valley’s (HHV’s) curatorial technician, delves into the woman behind the nickname and the mania she inspired.

In 1850, New York City was swept up in a kind of mania – Lind Mania to be exact. Known as the Swedish Nightingale, Jenny Lind was a 29-year-old soprano who wowed audiences across Europe with her stirring performances.

She arrived in Manhattan to much fanfare on September 2, 1850, on board the Atlantic. Newspapers like the New York Tribune and The Evening Post shared details of her transatlantic crossing and fed the excitement for her upcoming US tour. The papers also reported daily accounts of Lind’s activities, listings for tickets, and advertisements for Jenny Lind merchandise.

Retailers began to slap her likeness on everything. Cloak maker Brodel & Bell introduced a line of stylish evening wraps specifically intended for people planning to see Lind perform. Tuttle’s Emporium of European Fancy Goods offered “Jenny Lind music boxes, needle threaders,… balloons, and a host of other rarities.”

One of those bits of Lind-branded ephemera survives in HHV’s collections—Jenny Lind paper dolls. The Van Cortlandt family preserved the set, including six outfits for the diva to wear on stage – the 19th-century equivalent of a celebrity Barbie doll.

The Poughkeepsie Journal mocked the range of “Lindiana” which grew exponentially through Lind’s long tour by reporting that:

We had yesterday the pleasure of being shaved with a Jenny Lind razor, by a Jenny Lind barber, scented with Jenny Lind cologne, combed with a Jenny Lind comb, brushed with a Jenny Lind brush, washed in a Jenny Lind bowl, and wiped with a Jenny Lind towel. After which we put on our Jenny Lind hat, walked einto a Jenny Lind restaurant, and partook of Jenny Lind sausages. Then we took up a Jenny Lind paper, and read a Jenny Lind editorial, smoked a Jenny Lind cigar, and throwing ourself back in a Jenny Lind chair, fell into a Jenny Lind reverie.

Washington Irving certainly encountered Lind Mania. His publisher, Putnam, had imported a bust of the singer and advertised that it was on display in their offices. Advertisements for the latest editions of Irving’s works ran alongside those for Lind merchandise. At the end of October, Irving wrote to his niece Sarah Storrow expressing his skepticism of Lind Mania and his preference for music within the pageantry and context of an opera rather than a lackluster concert.

Within a week he had changed his tune. In a November 12 letter to his Sunnyside neighbor Miss Mary M. Hamilton, Irving wrote that he had “at once enrolled myself among her admirers” and “God save Jenny Lind!”

When Lind arrived in New York she had already been singing for 19 years, had appeared on stage in more than 700 opera performances, and was the subject of at least two biographies detailing her life so far. Promotor P. T. Barnum, already famous for his American Museum, saw an opportunity in Lind’s popularity and contracted her for 150 US concerts. For each performance Lind would receive the equivalent of $32,000 today. She would also be permitted to give charity concerts throughout the tour. The 2017 film The Greatest Showman depicted a highly fictionalized version of this tour (there is absolutely no evidence to suggest that Lind ever tried to seduce Barnum).

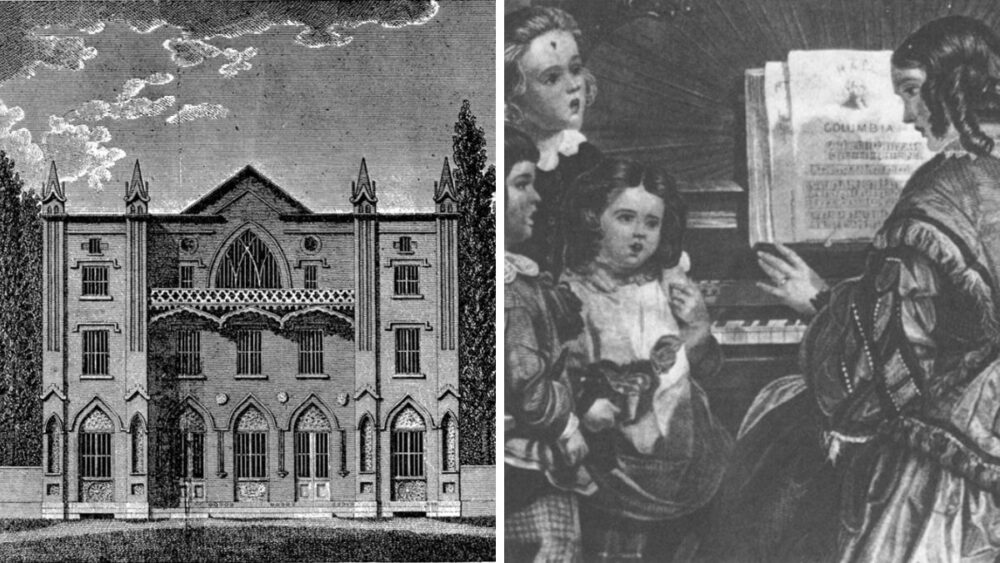

Lind’s first appearance filled the cavernous auditorium at Castle Garden on September 11, 1850. The Battery Park location, no longer extant, is depicted on a band box, or travel case, in HHV’s collection.

Lind ultimately parted ways with Barnum after 93 performances. She bought out the rest of her contract and produced her own tour through the United States and Canada. Lind performed her final concert on May 24, 1852, again at Castle Garden, before returning to Europe with her new husband, Otto Goldschmidt.

Far from simply a name linked to objects in a 19th-century marketing ploy, Lind was a savvy businesswoman who captured her American audience and profited from her own considerable talent.