A Stitch in Time: Exploring the Embroidered Artwork of Van Cortlandt Manor

In recognition of World Embroidery Day on July 30, Historic Hudson Valley’s Associate Director of Collections Jessa Krick shares this new information about an embroidered picture in HHV’s collection. World Embroidery Day celebrates the creativity of embroiderers around the world and the many inspirations for their work: joy, resistance, income, beauty, tradition, and storytelling.

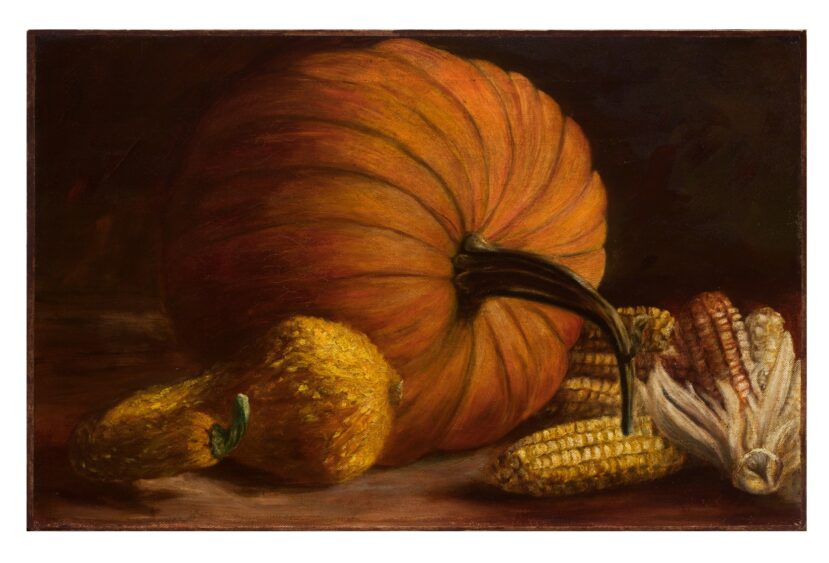

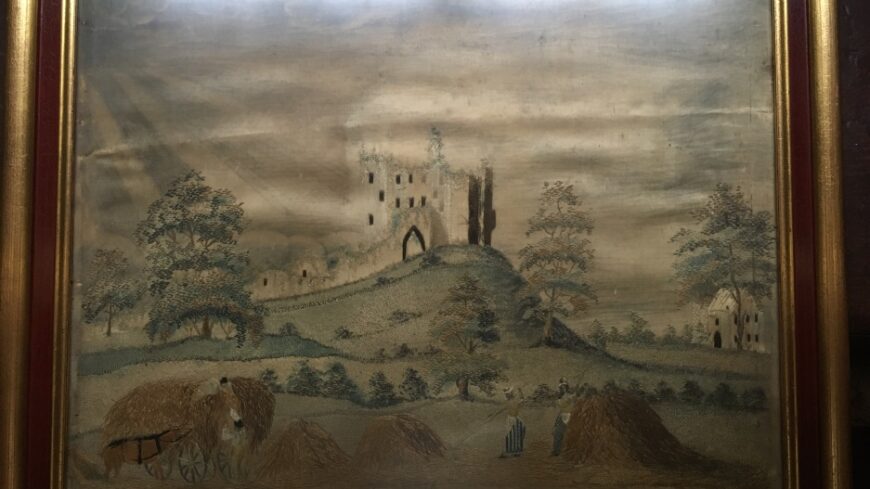

Long, hot summer days contribute to abundant hay harvests, just like the scene depicted in a silk embroidered picture that hangs in Catherine Van Cortlandt’s bedchamber at Van Cortlandt Manor. A gift to Historic Hudson Valley from Jean Mason Browne, the site’s last Van Cortlandt family resident, the landscape includes two women raking dry hay into a stack in the foreground, and two men (and a helpful—or hungry?— horse) load a cart nearby. A distinctive stone structure stands on a hillside overlooking the laborers below. Although many of the long satin stitches that comprise the tower are now missing, the form remains clear, as does the title written across the bottom: Dudley Castle.

Dudley Castle is an actual site in Dudley, West Midlands, England. Built in the 11th century and destroyed by fire in 1750, the romantic ruins made the site popular among artists and tourists in the late 18th century.

I often highlight this colorful piece during tours of the Croton-on-Hudson Manor House, where it hangs in an area protected by light but close enough for visitors to see the handiwork up close. It clearly was drawn and stitched after a print source, with details added in ink alongside the silk threads. And it looks just like the landscape prints that were produced in the 1780s and 1790s.

Since our sites have been closed during this health crisis, I found some time to search for a print that resembled it and found what I believe is the print source. I also discovered another very similar piece in the collection of Historic Huguenot Street.

While the identities of the two makers are unknown, the similar images and techniques evident in their work in the Dudley Castle embroideries suggest they may have been made by young women at an academy, such as the Union School of Albany (later known as The Albany Female Academy) where fine needlework and drawing would have been part of the curriculum. The students would have access to prints to use for inspiration and for studying how artists used perspective, for example, with an eye toward improving their own skills.

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, girls and women often incorporated fantastical plants or flowers and a creative use of scale when embroidering human and animal figures, but that changed as more printed images became widely available in the 18th century, especially in more formal settings where students worked to perfect their needlework skills. Samplers for practicing new stiches or techniques have been created through the centuries, with many incorporating religious or biblical quotations. Eventually we start to see more of the embroidered mourning pictures and formal landscapes. Even the color palettes reflect what we see in books of hand-colored prints dating to around 1800.

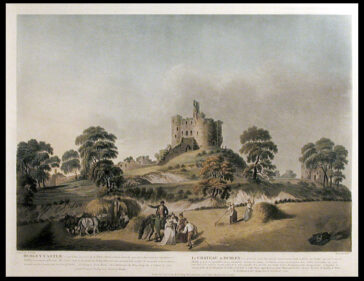

The print that appears to be the inspiration for the Dudley Castle embroideries is titled Dudley Castle/La Chateau de Dudley, published by Francis Jukes, September 10, 1793. Jukes produced the aquatint print in his London workshop along with several other views of picturesque ruins. The print, now in the in the British Library and several other collections, clearly shows the women harvesting, the men, cart, horses, and the castle. The nature of prints means that many copies would have been available, and popular sets were reprinted in multiple variations of size and color.

There is one significant difference between the British Library print and the embroideries: a central group of aristocrat observers has been cut from the scene. I imagine all those people would have been challenging to render. But so many of the other details are the same, down to the way the women are posed in the field.

Our needleworker, whoever she was, was looking carefully and translating a highly detailed work on paper into silk with her needle and threads.