From Dutch to English Law: One Woman’s Experience in Colonial America

By Elizabeth Turner, MA candidate, SUNY Albany

Margaretta (Happy) Rockefeller Fellow, Historic Hudson Valley, 2020

Historians commonly note the greater autonomy and legal capability that women in the Dutch colony of New Netherland experienced in comparison to their English counterparts. Importantly, Dutch law not only permitted women greater legal standing, but did the same for children as well.[1] Thus women such as Eva Philipse Van Cortlandt benefitted from the Dutch law before they could even walk. In Eva’s case, after the death of her father, Peter Rudolphus de Vries, a legal barrier shielded the child. Her mother, Margaret Hardenbroeck de Vries, was prevented from remarrying before she had ensured that the child’s financial well-being was protected.[2]

Following the 1661 death of her husband, de Vries, Hardenbroeck had sought to quickly remarry, not an uncommon practice for Dutch women during the 17th century. Remarriage for Hardenbroeck would further expand her family’s wealth and her ability to trade commodities between New Netherland, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Netherlands; as such, it is not surprising that Hardenbroeck pursued an usus marriage to Frederick Philipse, one in which she retained her own property and funds.[3]

In November of 1662, Hardenbroeck and Philipse petitioned the Orphanmasters Court to marry.[4] Charged with ensuring the legal and financial security of children in New Amsterdam, the court heard cases like this where the welfare of a child after the death of a parent might be in question. In response to the petition, the Orphanmasters required a detailed listing of everything belonging to Hardenbroeck and the deceased de Vries both in the colony and in the Netherlands. This type of inventory was not feasible to obtain within the eight days allowed.[5] Consequently, when Hardenbroeck returned to the court in December of 1662 with no inventory nor a contract that ensured Eva’s inheritance of her parents’ wealth regardless of the birth of other heirs or not, the Orphanmasters once again rejected the marriage and ordered Hardenbroeck to return to court with Philipse.[6]

Philipse and Hardenbroeck were more successful together, thanks, in part, to his promises, made with “special love and affection” to care for Eva even if her mother died before Eva did.[7] Fortunately for those involved, the Orphanmasters accepted this proposal to name Eva the heiress to the fortune of Philipse and Hardenbroeck, unless they produced another heir, at which point, she would receive a “fair half.”[8]

The fact that Eva’s adoption took place during the Dutch ruling of New Netherland is important and ensures her secure future: the Orphanmasters’ concern for the well-being of the child declined significantly during English rule. Eva’s life provides a case study of the way women and children were treated under Dutch law, in contrast to English law.

In 1700, Frederick Philipse had his will constructed to ensure his heirs received their proper due. As promised, in the aforementioned adoption agreement, Eva received one-fourth of her stepfather’s estate.[9] Philipse’s estate was divided into quarters and the other heirs included Philipse’s grandson Frederick,[10] his son Adolphus and his other daughter, Annetje.[11]

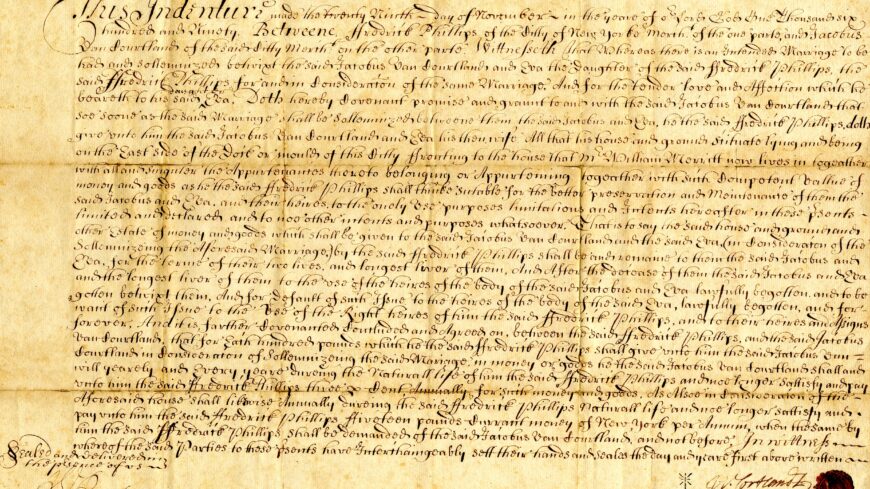

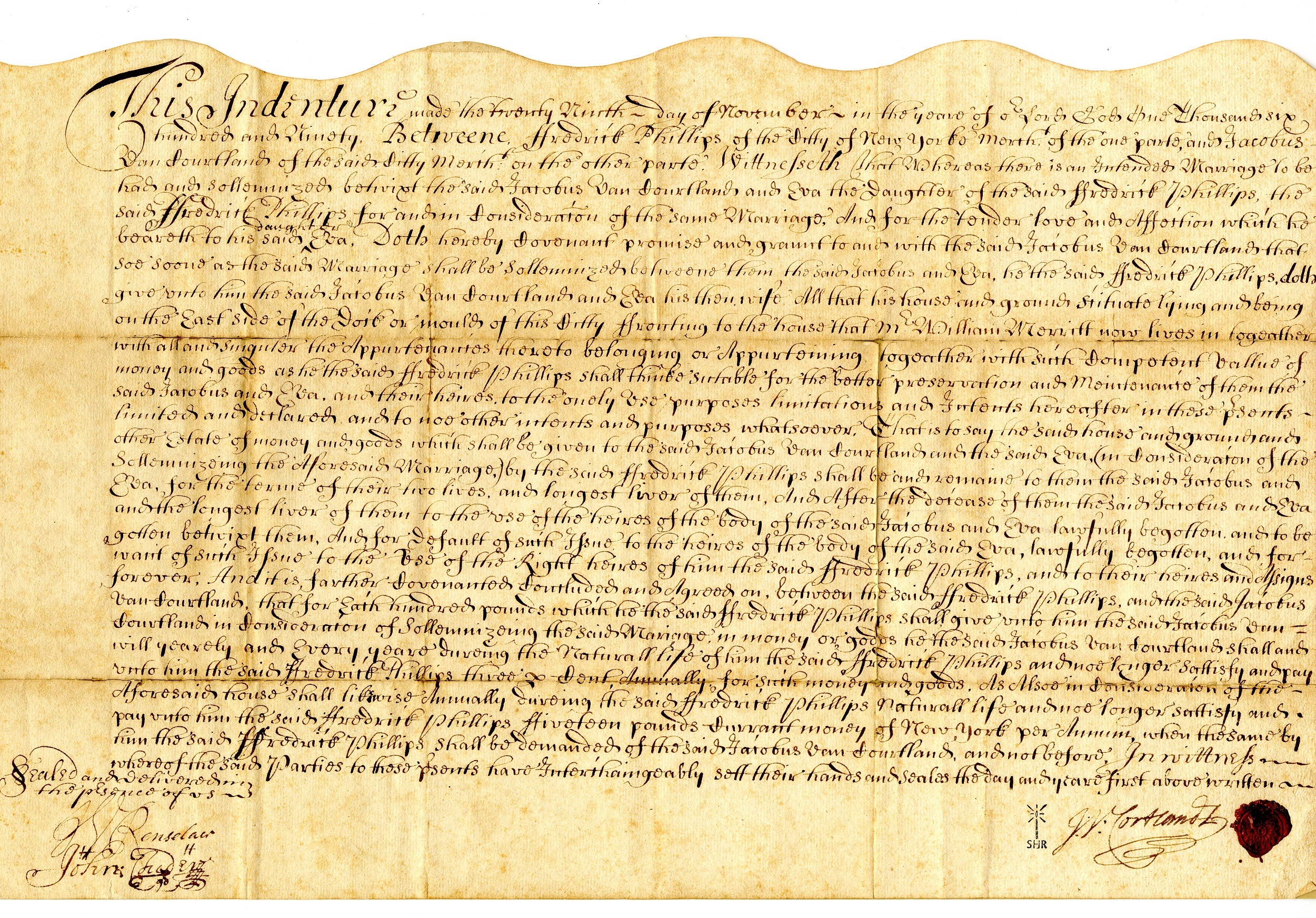

At the end of 1690, Eva prepared to marry Jacobus Van Cortlandt. An important aspect of the couple’s betrothal was the indenture between the couple and Philipse, spelling out not only details of where the couple intended to live, but also the business relationship between Philipse and Van Cortlandt. Somewhat surprisingly, the couple did not receive a gift of property outright upon marriage, but instead favorable lease agreements from Philipse.[12]

Although short, this contract contains some different phrasing than an earlier contract may have done. For example, Eva is described as “Eva, the daughter of Frederick Philipse” early in the document, but later she is referred to as “Eva, the wife of Jacobus Van Cortlandt.”[13] Given the period from which the document comes, the language that credits Frederick and Jacobus with custody of Eva is not surprising; nevertheless, for a Dutch woman of her status and of majority, the references to Eva are discouraging. As a woman of wealth and position, inherited from her parents—both successful merchants in New Netherland and New York—Eva was far more likely than other women to be credited with her own agency, yet that still ultimately is not what Eva experienced. While this is only one example of a woman’s involvement in a marriage contract, it reveals the limits that even women of influence encountered in transacting marriage. Women of lower classes at this time likely faced more difficult realities in regards to their legal standing.

In contrast with most Dutch men and woman of her class, Eva Van Cortlandt did not prepare a will before her death. As she died intestate, her property went without claims for years. In 1760, all that changed when her surviving children—daughters Mary, Anne and Margaret— made claims through their husbands.[14]

The rights of Eva’s daughters in 1760 were far different than those of their mother, one hundred years earlier. Upon marrying, Margaret, Anne, and Mary legally relinquished to their husbands whatever they might inherit.[15] As the usus marriage Hardenbroeck entered into in 1662 was no longer an option for women marrying under English law, any inheritance that might go to a woman in colonial New York went instead to her husband.[16]

These legal documents, showing changes that occurred over the course of a century, represent the difficulties women faced in the transition from Dutch to English rule in 17th-century New York. At the same time, many Dutch families still sought to care for their female relatives, as Philipse’s will demonstrates. Although English law did not protect women in the same manner as Dutch, the Dutch influence of the law is apparent into the 18th century. Eva Van Cortlandt is one example of a woman who benefitted from the security of the Dutch law that did not exist for her daughters.

[1] Susanah Shaw Romney, New Netherland Connections (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2014): 43.

[2] By ensuring the protection of orphans through the Orphanmasters Court, the colonial government prevented from becoming wards of the state, and a financial liability.

[3] This is in contrast to a manus marriage, where property is held communally. Robert W. Lee, Introduction to Roman-Dutch Law (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1953): 5-7.

[4] “Hardenbroeck v. The Orphanmasters.” Women and the American Story, New-York Historical Society, April 23, 2020, https://wams.nyhistory.org/early-encounters/dutch-colonies/hardenbroeck-vs-orphanmasters/

[5] “New Amsterdam, Minutes of the Orphanmasters Court, 1655 – 1664,” New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid. Additionally, this adoption contact stated that Hardenbroeck’s daughter “Maria” would be the heiress, so it also changed her name from Maria to Eva.

[9] Frederick Philipse Will, 26 October 1700, Coumbia University.

[10] Frederick II was the only child of Philip Philipse, Frederick’s eldest son. He was orphaned as a baby and brought from Barbados to New York; his grandmother Catherine Van Cortlandt Philipse was responsible for his care following the death of her husband.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Manuscript Collections of the Library of Historic Hudson Valley, Pocantico Hills, NY; P 251, Philipse Family Papers.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Petition from Abraham De Peyster, Peter Jay and John Chambers for letters of administration on the estate of Eva (daughter) of Frederick Philipse and widow of Jacobus Van Cortlandt (New York State Library, Albany, NY. “Eng. Mss. LXXXVIII, 10”) Photostat of fire-damaged, partial manuscript in the Collections of the Library of Historic Hudson Valley, Pocantico Hills, NY.

[15] By 1760, New York was governed by English law and two of Eva’s daughters, Mary and Anne, both married Englishmen.

[16] Albert E. McKinley, “The Transition from Dutch to English Rule in New York” American Historical Review 6 (July 1901): 695.