Letters, Locks, and Likenesses: How Nineteenth-Century Remembrance Practices Invite Us Into the Past

When we visit an archive, we are drawn into the world of people who lived long ago —and, oftentimes, we want to learn even more about them. I “met”’ Eliza Storrs through letters she wrote to Emma Nicholas (1816-1866), the last of which was written just two months before Eliza’s death in 1837. In her attentive letters, she detailed the social activities of mutual friends, referred to and quoted from contemporary poetry, and commented on letter-writing itself. For example, in September 1836 Eliza wrote that “when a letter comes then I shall feel that although separated, we are still united, and change of place will never change my affection for you.” She echoed what American novelist Hannah Webster Foster (1758/59-1840) explained in The Boarding School: letters are a “method of interchanging sentiments, and of enjoying intercourse with those from whom you are far removed, which is a happy substitute for personal conversation”i

Though being “far removed” from Eliza, with no means of a “happy substitute for personal conversation,” I eavesdropped on her side of a personal epistolary conversation. I learned she was a budding artist, taking classes with an instructor who also taught Washington Irving. I identified with her frequent commentary on being perfectly content not to marry. I admired her thoughtfulness when she included poems that she surmised Emma would like. Despite the time elapsed from Eliza’s death in 1837 to my birth in 1974, I longed to meet Eliza (an impossibility) or to know more about her (an improbability). Despite scouring records and databases, contacting various historical societies in New York State and Connecticut, these letters—and a stone block monument at Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven—seemed to be all that remained.

(SS.78.18)

However, thanks to nineteenth-century remembrance practices I did, in a sense, move a step closer to her. Three small boxes, filled with hair clippings deliberately placed into folded pieces of paper, are held in Historic Hudson Valley’s archives. In one box, Eliza’s dark caramel hair coils, a small loosening braid curving into a crescent about an inch long.ii Over successive generations, Emma’s descendants safeguarded the hair collection that tethered them to their loved ones. Now, thanks to the generous donation of Dorothy Neely Burton in 1966, we too can enter this intimate personal space.iii

Letters and Locks of Hair

While letters are an obvious example of contact, many nineteenth-century women exchanged locks of hair to maintain emotional connectivity as hair provided a substitute for the physical body. White, middle-class Americans partook in gifting hair or objects made from hair, such as wreaths, because of the view that hair “was the person whose hair was used” (emphasis added).iv Additionally, hair “embodied the sincerity of…individuals” and “demonstrated the emotions shared by the people involved.”v In June 1852 the posthumously famous poet Emily Dickinson wrote to her friend Emily Fowler, enclosing a gift: “I said when the Barber came, I would save you a little ringlet; and fulfilling my promise, I send you one today.”vi Fowler’s archives contain not only Dickinson’s hair but locks gifted by her other friends. This practice, as in Emma’s collection, began decades earlier and lasted throughout the nineteenth century.

Hairwork continues to engage us, even after its prevalence waned. In Independence, Missouri, Leila’s Hair Museum has collected and showcased nineteenth-century hairwork since 1986. Though a niche interest, with Leila’s Hair Museum being the only one of its kind, Historic Hudson Valley contributes to hairwork preservation through the hair that the Hoffman family women used to maintain connections during a time when absence—through physical distance and death—ruptured relationships.

Miniature Portraits and Hairwork

While entranced by the Hoffman tress collection, another object attracted my attention: a miniature portrait of Josiah Ogden Hoffman (1766-1837), the grandfather of Eliza’s friend Emma.vii The back of the oval portrait case reveals brown hair crossed under glass and the initials S.M.H. Presumably, these initials refer to Emma’s aunt, Sarah Matilda Hoffman, who was engaged to the author Washington Irving at the time of her death in 1809. I was stymied by the specifics of who would have owned the portrait, whose hair was encased on the back, and why the initials would have been of Hoffman’s daughter and not the subject of the portrait itself. The history of miniatures could help answer these questions.

(SS.85.5)

Miniature portraits became popular during the latter half of the eighteenth century, a tradition brought to America by British colonists, and they became popular among not only wealthy but aspirant middle-class members.viii According to Robin Jafee Frank, miniature portraits served as private tokens, to be shared among family members as tokens of love distinct from the large, public portraits commissioned to hang on walls. Further, these “private tokens” also “emblematically kept the absent family member within the circle of the living.”ix During the Victorian era, jewelry containing hair became important mourning objects, and women would typically wear miniatures to publicly show private devotion.x

While I can only theorize who owned this item, custom suggests two possibilities. The miniature may have belonged to Josiah Hoffman’s second wife, Maria Fenno (1781-1823). Both Josiah and Maria had other small portraits completed by well-known miniature portrait artists, John Ramage and Thomas Sully, during the art form’s popularity in the 1790s and early 1800s.xi While Matilda was not Maria’s biological daughter, she would have been eleven years old at the time of her father’s second marriage. This would certainly have been young enough for the two to establish a relationship and for Maria to mourn Matilda’s passing. Or the miniature could have been the possession of Hoffman’s daughter Ann, who sought to honor her father and her sister’s memory. While the object’s ownership is uncertain, we can theorize that the idea of mourning the loss of a daughter or sister amid marital love or filial devotion occasioned this miniature portrait. As Frank explains, “Regardless of whether the sitters’ accomplishments remain memorable to us today, the existence of their likenesses in miniature means that somebody cared deeply about them. Often the reason for the portrait was never known publicly or has been lost.”xii Until future archival discoveries provide clear answers, we can only be sure of one thing: that these people mattered enough to have their likenesses and their hair preserved for hundreds of years by descendants and now archivists.

Conclusion

Reading letters is an intimate act, and researchers feel the tension of violating privacy and knowing that archived letters can yield great insights into a different time. The same apprehension occurs with non-textual objects. But personal items maintain individual legacies of people—oftentimes women—who were not afforded a public presence. Similar to my experience, the artist and art historian Jane Wildgoose became entranced by a simple lock of hair and small portrait of Ferdinand de Rothschild’s wife Evelina, choosing these mourning artifacts as a focus despite the numerous paintings and grandeur of his estate.xiii As families used the tools of mourning and memory to keep family members alive across the generations, so too can we continue to remember those who have gone before.

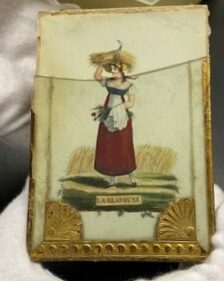

As curator Caitlin Monaco delicately returned Eliza’s hair to its container, I took one last look at the box’s illustrated cover. A woman stands gazing to her right, one hand holding grain atop her head, her other hand clasping flowers nestled into her white apron. Her nearly bare arms hold both bundles steady, her red skirt—long and straight—stops just above her feet which appear paused mid-step. She is identified only as La Glaneuse. She is the gleaner, one who gathers. The Hoffman women, too, deliberately gathered small pieces of their family, their legacy, and their history for us. It is our responsibility to carry on this work.

Cheryl Weaver was the 2023 Margaretta (Happy) Rockefeller Summer Research Fellow for Historic Hudson Valley’s Women’s History Institute. Weaver holds an M.A. in English, an M.Ed. in English Education, and is currently finishing a dissertation toward a Ph.D. in English at the University at Buffalo. In 2022, Weaver received the Emily Dickinson International Society Graduate Fellowship in support of research related to the dissertation “‘You know it is customary’: Emily Dickinson and Nineteenth-Century Epistolary Practice.” Most recently, Weaver presented on Margaret Fuller’s use of the international post at the 2022 Thoreau Gathering and “Postal Horizons: The British Postal Service in Richardson’s Pamela and Haywood’s Anti-Pamela” at the 2022 Epistolary Research Network Conference.

[i] Foster, Hannah Webster. The Boarding School; Or, Lessons of a Preceptress to Her Pupils . . . by a Lady of Massachusetts.. Boston: 1798, 32.

[ii] Historic Hudson Valley Collections, SS.78.18, Gift of Dorothy Neely Burton.

[iii] Emma’s daughter Anne Maloney Neely first maintained her mother’s items; in 1966 Emma’s great-granddaughter Dorothy donated the collection to Sleepy Hollow Restorations, Inc., which later became Historic Hudson Valley.

[iv] Sheumaker, Helen. Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011, viii.

[v] Ibid., viii.

[vi] Dickinson, Emily. Letters of Emily Dickinson. Vol. 1. Massachusetts: Roberts Brothers, 1894, 1894. The letter is located in the Emily Fowler Ford Papers. General Correspondence Box 16, Folder 6. Archives & Manuscripts, New York Public Library.

[vii] Historic Hudson Valley Collections, SS.85.5, Gift of Dorothy Neely Burton

[viii] Frank, Robin Jaffee. Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Art Gallery, 2000.

[ix] Ibid., 7.

[x] Sherrow, Victoria. Encyclopedia of Hair: a Cultural History. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2006.

[xi] John Ramage, portrait miniature of Josiah Ogden Hoffman, ca. 1790, on ivory, 1-3/4”-1-1/2, formerly in the collection of Phoebe Hoffman Bickerton, NY, NY; Frick Photoarchive: https://digitalcollections.frick.org/digico/#/details/ContainerID/b10989997/All.; Portrait of Maria Hoffman (nee Fenno 1781-1823), by Thomas Sully (British, 1783-1872), titled and marked verso. SS: 35″ x 26″, OS 35″ x 26″, OS: 43″ x 34″: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/62/Portrait_of_Maria_Hoffman_%28nee_Fenno_1781-1823%29.jpg

[xii] Frank, 13.

[xiiii] Wildgoose, Jane. “Beyond All Price: Victorian Hair Jewelry, Commemoration & Story-Telling.” Fashion theory 22, no. 6 (2018): 699–726.