Letters From Our Collection: A Revealing a Portrait of Sender and Recipient

I sometimes wonder what a stranger could learn about me by scrolling through my email inbox. What do the messages from companies and organizations, friends and family, say about the interests and relationships that are important to me? This might seem like a strange line of inquiry, but it gets at a broader question: what do the messages we receive say about who we are and the record we will leave behind? As someone with an interest in historical correspondence, this question is often on my mind. In my experience, a message can say as much about the recipient as the sender.

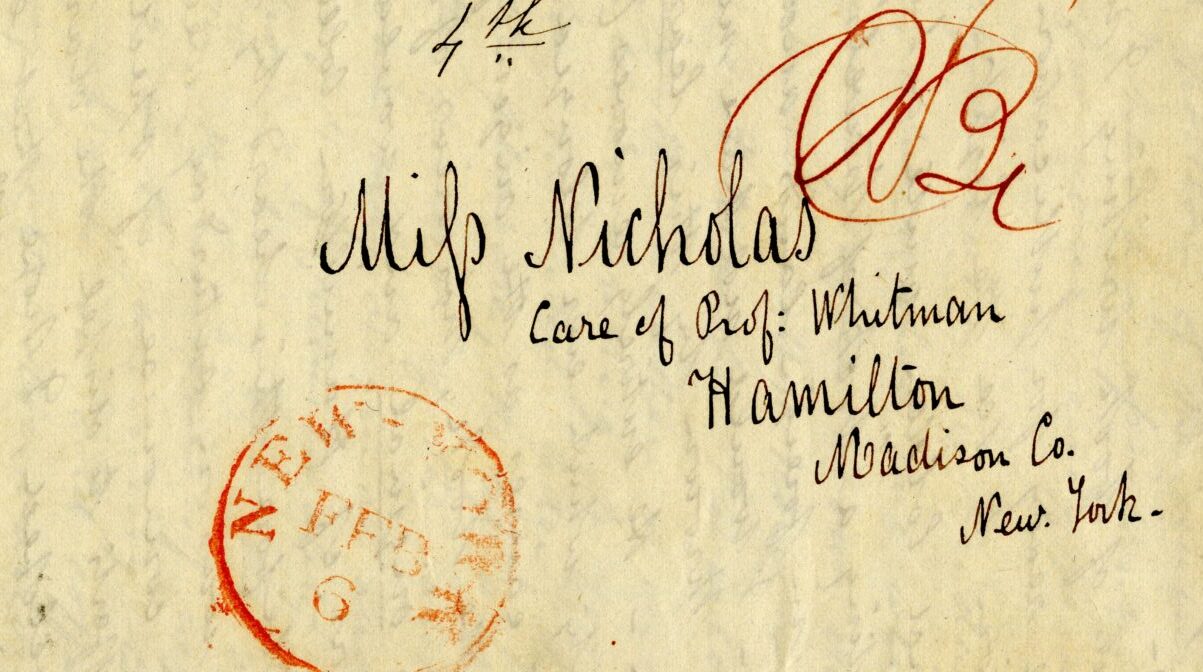

This was the case during a recent internship with the Women’s History Institute at HHV, when I studied a 19th-century correspondence between Philip Rhinelander and his cousin, Emma Nicholas. As I read and transcribed Philip’s letters, I learned about this young man of an old New York family who possessed a biting wit and a penchant for digression. Through Philip’s eyes, I also learned about Emma, the recipient of the letters and an exacting correspondent and loyal friend.

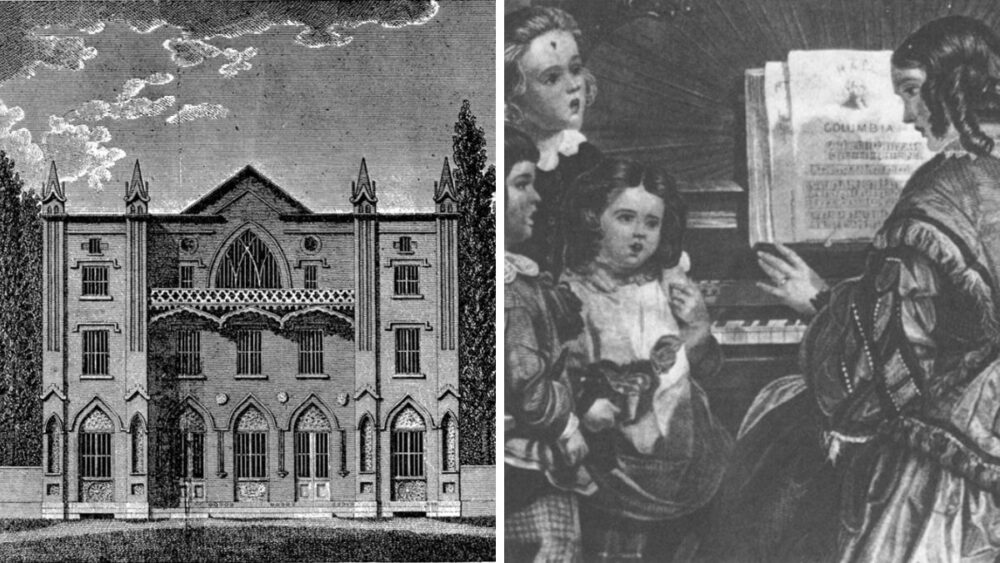

I first met Emma in an 1825 letter that Philip sent to her when he was a young boy, and she was away attending boarding school. As I transcribed the letter, I learned that Philip missed his cousin. He asked when she would return home to play “Lion and Whale” and when they could visit their favorite lake again. From the letter, it was clear that both were imaginative and lively children, deeply connected to their friends and family at the Rhinelanders’ bucolic home in Hell Gate, now the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

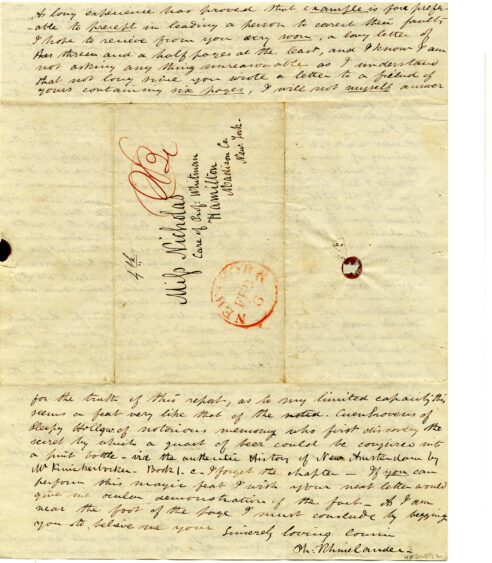

Written in a childish chicken scrawl, this letter was one of the easiest to transcribe. Once Philip grew up, however, he adopted the conventional but convoluted penmanship of the time, an elaborate cursive. This meant that transcription required a careful process. I would read each letter once for content, again as I typed it up, and a third or fourth time to figure out some of the words I couldn’t discern before. This process mirrors the effect of carefully brushing the dust of some unknown artifact, slowly discovering what it is and the significance it holds, a meticulous but rewarding process.

Through this process of transcription, I watched Emma and Philip grow up. By 1835, Philip had graduated from Columbia, and Emma had moved to Kishwaukee, a town near present-day Rockford, Illinois, where she would start a family and a new life. Philip begins a letter from this period by addressing Emma’s complaint that “my letters were so much like essays and contained so little information as to ruffle even your generally even temper.” Clearly, Philip prefers to describe his world in a literary, meandering style, while Emma prefers a concise narrative that focuses on conveying facts. Philip is something of a romantic, while Emma is a pragmatist. In small details like these, his letters slowly reveal a portrait not only of their author, but of their recipient.

These portraits come into focus as Philip reveals the differences in their worldviews, but also the similarities. Many of these similarities are rooted in their shared memories. Later in the same letter, Philip reflects on Emma’s recent move, explaining, “I imagine the country to be much like the Lake.” He refers to the same lake the two visited as children, the one he mentioned in the 1825 letter. This lake is a recurring motif in his letters, often mentioned when he reminisces about their childhood. For both, this nostalgia seems to be tied to the memory of a time when they weren’t separated by the hundreds of miles between New York and Kishwaukee.

When I started the internship, I didn’t realize how many embedded narratives one letter could contain – not only the narrative of the author, but of the recipient and all the other characters the letter mentions. Philips’s letters tell his story, but they also add to the narrative of Emma’s life and the lives of many others in their circle of family and friends. His story includes Emma’s, but also the story of Eliza Storrs’s parties, of Mary Rhinelander’s “coming out” into polite society, and much more.

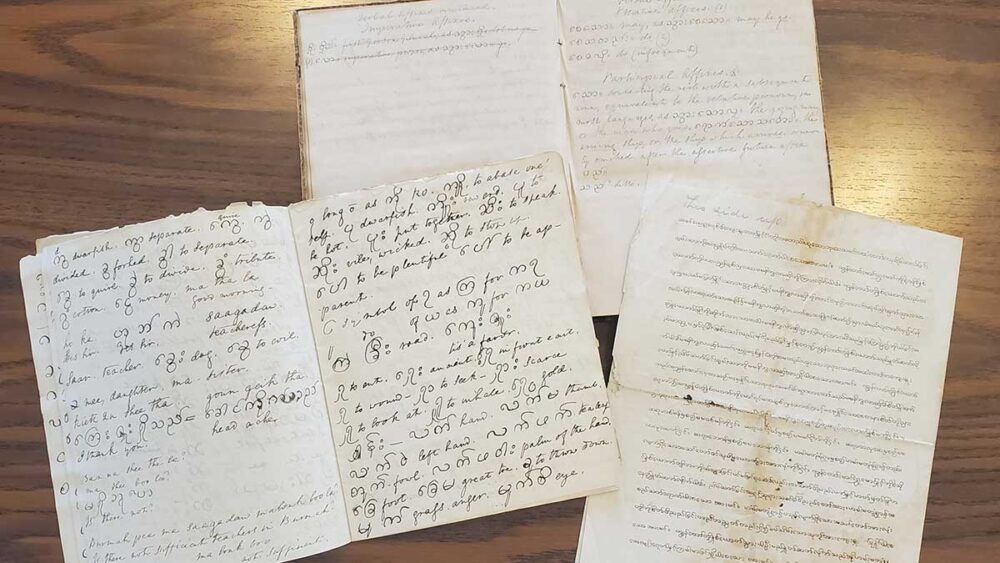

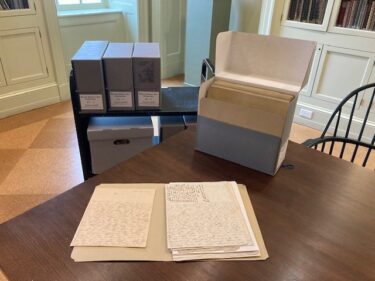

At the end of the internship, I visited Sunnyside, the estate of writer Washington Irving who was a close friend of the Rhinelander family. Sunnyside is owned and operated by HHV and the letters are housed in its Library. Until that point, I had only worked virtually with copies of the letters, so librarian Catalina Hannan laid out all the original letters to show me in person. Arrayed across a large table, the letters reassembled a puzzle with each letter being a piece.

Though each letter represents just a small piece of history, over the course of the internship, I came to view every letter as its own puzzle. Taking pieces from Emma’s life, from his own experiences, from the world around him, each of Philip’s letters is a complicated, interlocking web of stories. I see transcription as the process of puzzling together those stories.

Grace Ellis

Virtual Intern