There Were Pirates at Philipsburg Manor…Really???

What’s the connection between the heritage of Philipsburg Manor, an 18th-century Sleepy Hollow historic site once operated by slave labor, and piracy? Plenty.

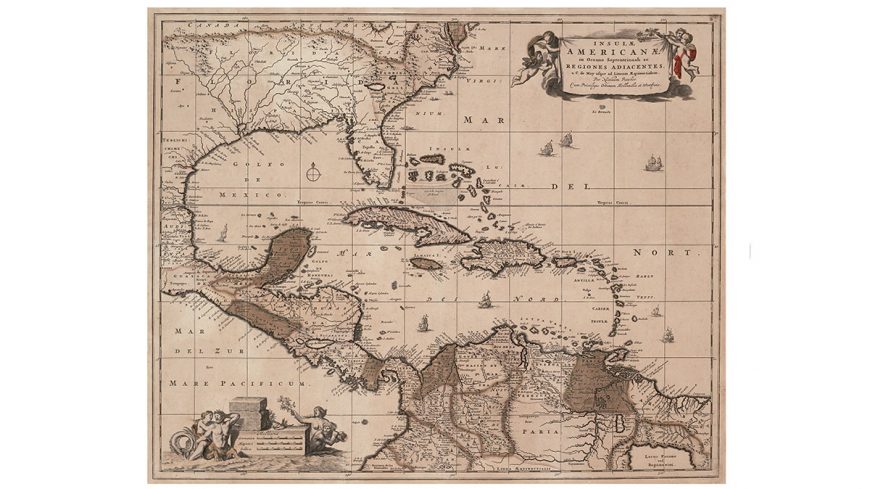

Though pirates have always been a concern for sailors on the high seas, the so-called “golden age” of piracy flourished in the latter part of the 17th and early part of the 18th century. Merchants like the Philipses faced danger from pirates who preyed on boats large and small, and from privateers like Captain Kidd, who, during wartime, practiced a form of government-sponsored piracy in which privately-owned boats were commissioned by governments to attack and rob enemy vessels.

The Philipses had associations with illegal trading and piracy as both victim and beneficiary, while the Hudson Valley was rife with piracy in general.

During the Nine Years War (1689-1697, a.k.a. King William’s War) between England and France, French privateers disrupted profitable European trade routes, capturing commercial vessels of Britain’s colonial merchants. Indeed, two of the Philipse’s boats, loaded with valuable commodities (including hundreds of beaver skins), were captured by privateers before reaching the English Channel.

Looking elsewhere for profitable trade, the Philipse’s turned to the growing slave trade with Madagascar. While the Royal Africa Company enjoyed a monopoly on all trade west of the Cape of Good Hope, slaves were cheaply obtained on the east coast, a trade which was also ostensibly legal due to loopholes in the charter of the East India Company.

By the 1690s the Island of Ste. Marie, just off the northeast coast of Madagascar, had become a locus for pirates preying on Indian, Muslim, and, occasionally, East India Company vessels in the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. An Englishman named Adam Baldridge established a fortified encampment there and set himself up as a factor, purchasing goods from pirates and selling them supplies. In 1691, Baldridge wrote Frederick Philipse offering him slaves at “30 shillings a head.” Between, 1693 and 1699, Philipse sent his ships on five trading voyages to Madagascar, carrying goods that were clearly intended for sale to pirates there (probably via Baldridge). Unfortunately for Philipse, the last two voyages were ill-fated.

In 1698 the New York Merchant returned from Madagascar carrying 70 slaves and assorted goods. Before it entered New York harbor, it was met by Adolph Philipse, who had its cargo loaded onto the Frederick and taken to Hamburg, Germany (certainly to avoid import duties, and possibly also because these other goods, including silks and spices, evinced illegal trade with pirates). In Hamburg, the official British resident, Paul Rycaut spotted the questionable goods and the Frederick and her bounty were confiscated as a violation of the English Navigation Acts. Although Frederick Philipse eventually got his ship and her rigging returned, he lost all of the East India goods and he was profoundly embarrassed. The Board of Trade ordered that he be removed from the Provincial Council and “from all other places of publick trust in the government whatsoever.” Adolph Philipse was also banned from holding public office.

Shortly thereafter, the British navy stopped the Margaret, another Philipse-owned ship, and arrested its captain, Samuel Burgess, while pirates seeking amnesty in New York jumped overboard. They were caught shortly thereafter and found to have with them 11,000 pounds of currency. Adolph stayed in London for two years and fought for and won the eventual release of Captain Burgess, but lost the ship and its contents (including 114 slaves). Frederick Philipse died a few years later, and Adolph rebounded from this episode to become one of New York’s most powerful merchants until his death in 1750.