Sojourner Truth: A journey from enslavement to inspiring speaker and human rights advocate

By Jessa J. Krick, Associate Director of Collections, Historic Hudson Valley

Snow blankets the ground at Philipsburg Manor and the property slumbers. At this time of quiet, many of us planning for the season, and finding new ways to share information and our sites.

This spring and summer, we will greet visitors to the Sleepy Hollow plantation and mill complex through our tours, teachers’ institute sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities, and via our interactive documentary website, People Not Property: Stories of Slavery in the Colonial North.

At the heart of our work are the true stories that make historical events come alive and resonate with 21st-century visitors long after they’ve headed to the next Zoom class or Netflix screening.

One of the stories I’ve been thinking about recently is that of Isabella Baumfree, who was born in Esopus, New York, at the end of the 18th century. Most people know her as Sojourner Truth, the name she took to shed her enslaved past and create a new life. You can find more information about her on People Not Property.

Sold away from her family around the age of thirteen, Isabella endured severe punishments and injuries. As a young mother, she fled her enslaver and found shelter and support with abolitionists not far north of Philipsburg Manor, in Kingston, New York. With their help, she emancipated herself and her infant daughter. In 1828, Isabella fought for and won custody of Peter, another of her five children, who had been illegally shipped to Alabama where he would have remained enslaved for life.

Isabella experienced the first of two religious awakenings in 1843, inspiring her to adopt her new identity as Sojourner Truth. She also found a calling as an orator, making impassioned speeches in favor of abolishing slavery and granting women the right to vote. Despite being illiterate, she held numerous speaking tours, found many allies, and helped persuade hostile audiences with her earnestness and the power of her plain-spoken, Dutch-inflected language.

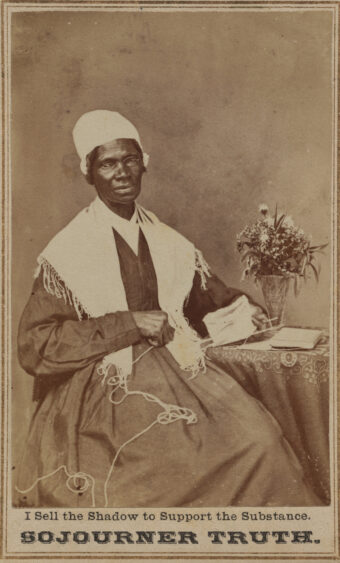

Sojourner Truth supported herself by selling her likeness, often in the form of carte de visites, or small photographs mounted to a heavy card. A personal message was printed on many of the cards as she established her speaking career in the 1860s: “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”

The woman who had once been someone else’s property now shared a message under the new legal protection of copyright, which allowed her to sell her own photographic image and use those proceeds for her welfare and the causes she held dear.

Given her distribution methods, Truth’s portraits are plentiful and survive in the collections of several American museums. Many of the photos—she sat for at least eleven portraits—show her knitting, the light-colored yarn trailing from her right hand, and a knitted work-in-progress in her left. According to an expert knitter and colleague at HHV, Truth’s work looks to be something practical—the top of a stocking or an undersleeve—knit on four needles.

For scholars of Truth’s portraits, though, the symbolism is great. Truth’s handiwork conveyed an aspect of her social justice message, that knitting represented industry and advancement. She demonstrated the skill to people she met, many of them seeking refuge in the Freedmen’s Village in Washington, D.C., in the mid-1860s, and encouraged them to take up knitting. Her audience might produce items they sold or kept for themselves. Regardless, she believed that anyone would be “much happier” if usefully employed.

It was though a recent podcast from the National Gallery, however, that I learned something about one of the frequently reproduced Truth portraits. As Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw points out, a loose end of yarn draped on Truth’s dark skirt forms the shape of the Eastern seaboard from Maine to Florida. This deliberate arrangement represents Truth’s audience, the country as a whole. “It says, ‘I am speaking to the nation when I present myself visually’” Shaw said. And to me, it refers to the all-encompassing sweep of Truth’s message—freedom and equality for all, in states North and South.

Truth’s message is very much still a work in progress and her words are worth revisiting today, 195 years after she freed herself and began to channel her experience of enslavement into a powerful message on behalf of human rights.

. . .

For more information about Sojourner Truth’s skillful use of language, watch this short, animated film written by Dr. Daina Ramey Berry, a friend and scholarly advisor to Historic Hudson Valley. It is produced by TED-Ed and available here.

Visit the memorial statue of the young Isabella Baumfree by artist Trina Greene, at Sojourner Truth Memorial Park in Port Ewen, New York, at the junction of Route 9W and Salem Street.

Visit the new memorial statue of the adult Sojourner Truth by artist Vinnie Bagwell, at the Walkway Over the Hudson Visitor Center in Highland, New York.

Sources:

Grigsby, Darcy Grimaldo. Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadow and Substance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

–. Sojourner Truth, Photography, and the Fight Against Slavery. Berkeley: UC Berkeley Art Museum, 2016.

Mabee, Carlton. Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend. New York: New York University Press, 1995.

Sajet, Kim “Seeing Truth with Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw.” Portraits: Real People, Real Stories. Podcast audio. December 1, 2020. https://npg.si.edu/podcasts/sojourner-truth.