Thomas Commeraw, Free Black Potter of New York

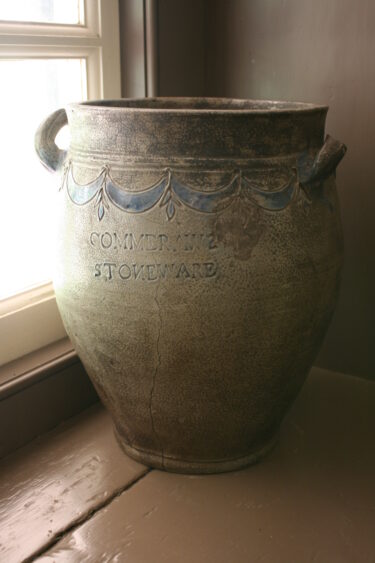

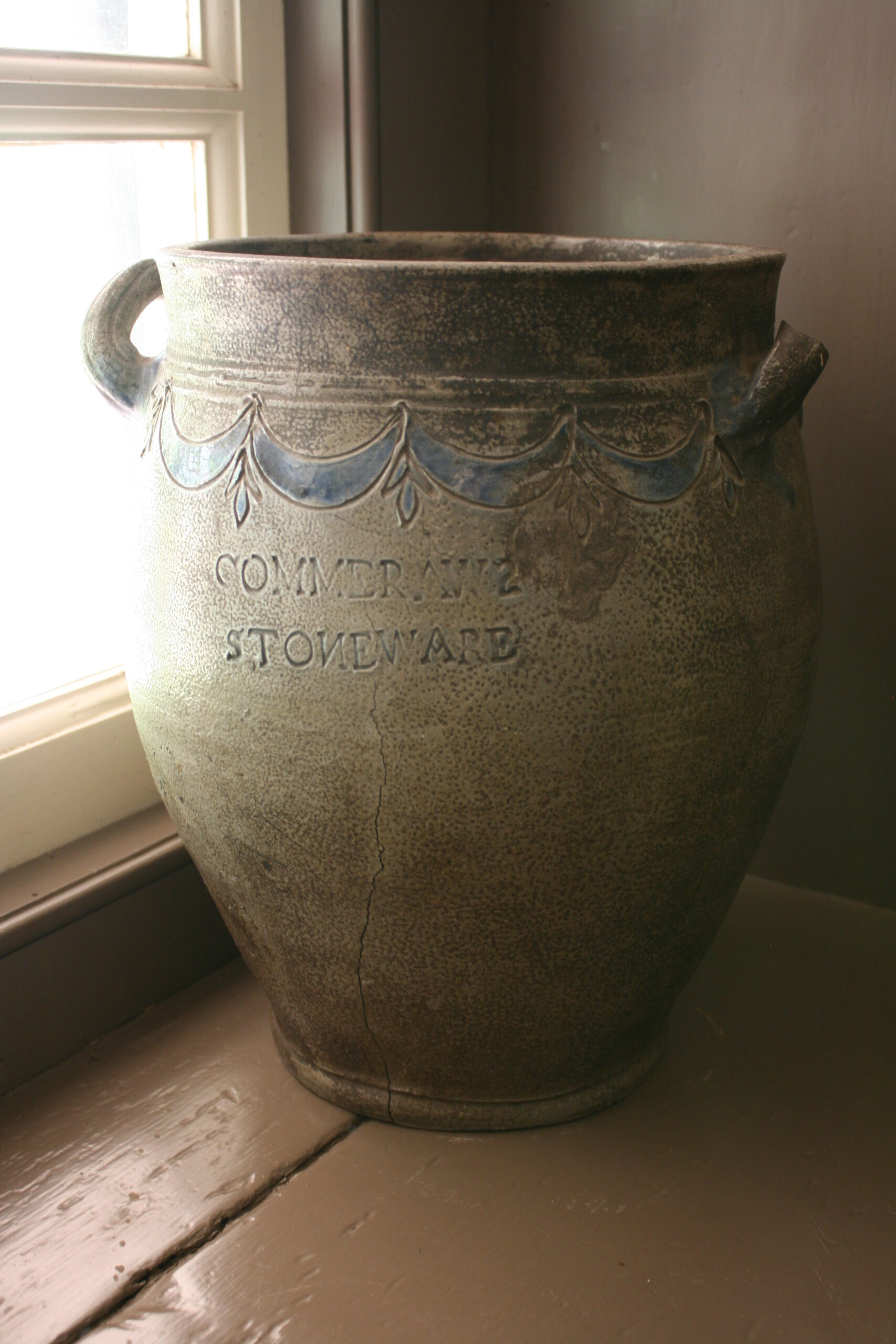

A large jar made in the workshop of Thomas Commeraw. New York, 1810-1820. Stoneware. Historic Hudson Valley (VC.59.16X).

Tucked into a corner of the milk room at Van Cortlandt Manor, a large ovoid stoneware jar rests on a plank bench as if waiting for Philis, an enslaved woman, to pack it with vinegar, salt, and cucumbers from the kitchen garden. Blue glazed details stand out on the tan body, as does the one remaining handle. It’s flattened at the ends, where the maker’s fingers pressed the clay to the vessel before sending it to the kiln for firing.

Stoneware was essential in the 19th century. The regular utilitarian containers were used over and over, particularly for food storage in an era before tin cans and glass jars, and long before single-use packaging.

This piece, however—as well as two others from the collection at Van Cortlandt Manor—are of note because they came from the workshop of Thomas Commeraw, a free Black potter in early 19th-century New York. All the pieces at Historic Hudson Valley bear stamped letters spelling out Commeraw’s name, which was a means of marketing at the time. His boldly marked surviving pieces are easy to spot, but that did not prevent 20th-century scholars from misidentifying Commeraw as white and “possibly French.”

Now, thanks to the efforts of a new generation of researchers, much more is known about the potter, who was a business owner, landowner, and church leader. He would eventually be a passenger on the Elizabeth, the first ship to leave New York for Sierra Leone in 1820 with the American Colonization Society (ASC). Founded to promote the manumission of the enslaved and the settlement of free Blacks in West Africa, the relocation plan advocated by the ACS was highly controversial in the Black community. Frederick Douglass said Black Americans should stay in America, which was their nation as much as anyone’s, and fight to improve their status. Others believed in making a new start in Liberia and that enjoying true freedom in a nation that allowed slavery was impossible.

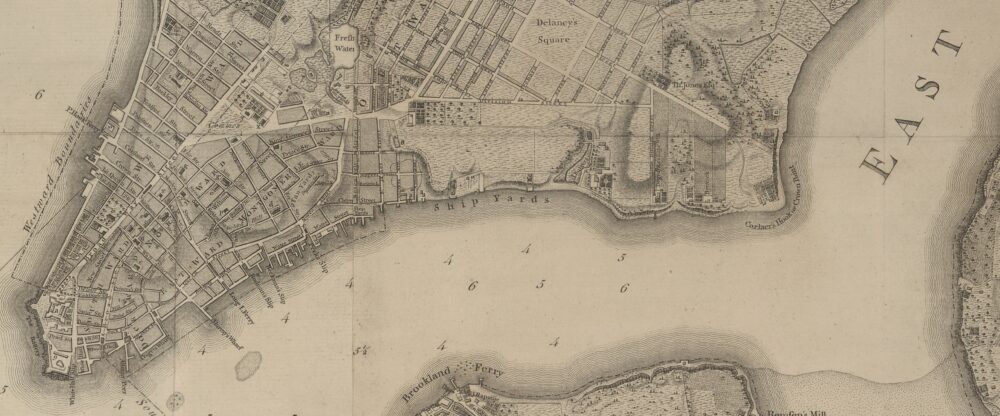

The HHV collection includes two jars and a jug made in Commeraw workshop in Corlear’s Hook, in lower Manhattan. All three date to the later period of his productivity in New York, when the swag-and-tassel motif featured prominently in his work. An oyster jar, for which Commeraw was well known, would be a prized addition to the collection. “They date to around 1810, a time when Commeraw clearly appears to have been supplying the free Black oystermen of New York with this specific vessel in order to sell their hauls of shellfish,” said Jessa Krick, Historic Hudson Valley’s Associate Director of Collections. “Free Blacks were restricted in the kinds of work they could do, but feeding fellow New Yorkers was a means of making money and where members of the Black community excelled.”

A larger body of knowledge about Commeraw is coming to light, including his efforts to build fortifications in Brooklyn during the War of 1812, and evidence of his role within his religious community. Mark Shapiro, a potter who has been researching Commeraw for years, believes that a combination of debts and an evangelical zeal led Commeraw and his family to make the voyage to Sierra Leone. Commeraw’s experience, recording in letters and reports of the enterprise, showed the difficulties of the colonization effort. The settlers lacked food and water and suffered from malaria. Some of the group died from fever in their inhospitable landing place. Commeraw lost his wife during the sojourn. He and his children survived the ill-fated voyage and returned to New York in 1822, but it seems, the potter never again made stoneware.

That tragic trip is just one part of Commeraw’s story. “This man was making the highest quality of pots that stand next to the best pots of the time, and [he] was doing amazing work in an environment that was not easy…. I want to bring that [story] to the larger world,” Shapiro said in a recent podcast. Added Krick: “Scholarship about Commeraw has evolved and so much more is coming, with books and exhibitions in the works right now. Historic Hudson Valley’s objects are a part of that body of work.”