A History of Jigsaw Puzzles — Plus Try Your Own!

Little did cartographer John Spilsbury know that when he first pasted one of his maps atop a piece of wood and cut it into pieces that his creation would produce a centuries-long puzzle craze—and that the jigsaw puzzle, as we now call it today, would reflect many of the social, cultural, and technological changes from the 18th century to the present. Spilsbury originally intended his “dissected maps,” introduced in the 1760s, to be educational tools to learn geography. At the time, maps were something of an obsession for European leaders, and the idea of carving the globe into pieces corresponded with the colonialist attitude held in royal courts. The children of King George III and Queen Charlotte, the future Kings George IV and William IV, played with these puzzles as young princes. (For more about trade and colonization, visit Historic Hudson Valley’s online exhibit Traders and Raiders.) Gradually, puzzles moved beyond geography as British manufacturers expanded to other subjects that were considered important in the 19th century, including history, the alphabet, and scripture.

These wood-backed puzzles, cut into interlocking pieces, first appeared in America in the middle of the 19th century, as educational tools rather than the recreational pastimes that we think of today. It is likely that puzzles would have been one form of educational engagement enjoyed by Washington Irving’s family at Sunnyside. Irving’s great-niece Little Kate wrote about doing her lessons while visiting the cottage in 1854, and we can imagine her in the parlor, doors overlooking the Hudson River, perhaps playing with a puzzle on the floor of the room, perhaps a hand-me-down from some of her older cousins.

The decades after the American Civil War saw new developments for this puzzle. Toy companies like Milton Bradley, founded in 1860, and Parker Brothers, founded in 1883, began producing puzzles that were more entertaining in content. Some businesses began creating puzzles as promotional tools. A puzzle in Historic Hudson Valley’s collection was produced by the apothecary CI Hood & Co to promote its sarsaparilla medicine. Technological changes also contributed to the production of these puzzles. The invention of the treadle jigsaw (powered by someone’s foot pressing on a pedal) enabled the cutting of intricate shapes more easily. Because the movement of a treadle jigsaw is similar to that of a sewing machine of the time, companies like Parker Brothers hired women as jigsaw cutters. (Hiring women for this work also meant that the companies paid less in labor, as women were not paid as much as men.)

As puzzles began to feature more entertaining rather than solely educational content, they became a common pastime in American households into the early 20th century. Puzzles enjoyed a surge of popularity during the Great Depression as an affordable form of entertainment. By this time, the lithographic process allowed images to be published more quickly and cheaply, mounted onto inexpensive plywood, and die-cut by machine. During World War II, with plywood in short supply, cardboard became the new mount for puzzle pieces.

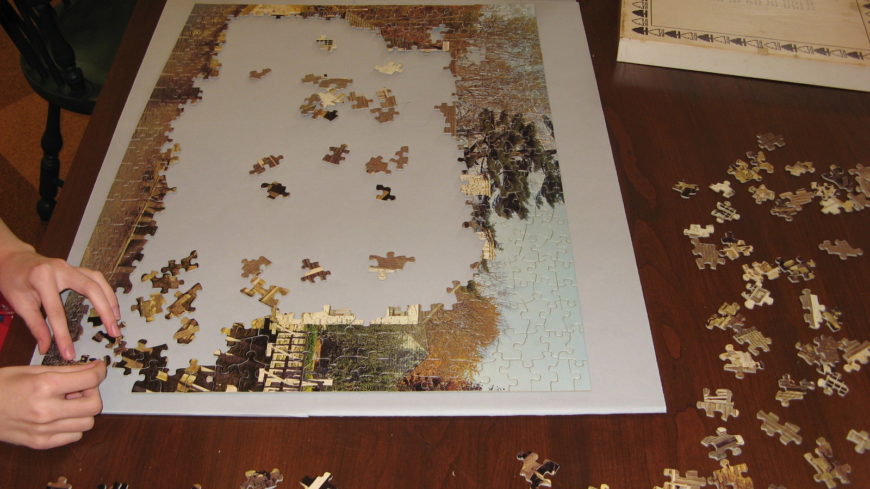

In the 1950s, the rise of the television as in-home entertainment led to a decline in the popularity of puzzles. Still, puzzles remain a source of family fun, as manufacturers find ways of using contemporary TV shows, movies, or other pop-culture phenomenon for puzzles. Additionally, puzzle makers have begun creating highly difficult puzzles, including monochromatic puzzles, puzzles without border pieces, or optical illusions in puzzles. Some puzzles are also part of a larger game, with clues or storytelling elements hidden in the puzzle’s picture. In these cases, finishing the jigsaw puzzle is only the first step in solving a mystery. Despite the many changes in this form of entertainment over time, for many children today, puzzles are one of their very earliest educational toys. Farm animals, shapes and letters, states and countries continue to be found on brightly-colored foam and wooden puzzle pieces in many nurseries and children’s play areas.

At Historic Hudson Valley, we always strive to provide a mix of educational and entertainment experiences, and we hope you enjoy exploring our sites through these digital puzzles.