A New York Manumission Story from Our Manuscript Collection

Transcribing letters from two centuries ago is much like archaeology; the reader carefully sifts through words eagerly anticipating what treasures might await. Often these little paper miracles, somehow saved and salvaged over the years, can, as one of my correspondents charmingly penned, introduce us to “the very shovel and tongs of [the writer’s] fireplace.” However, within such beautiful intricacies of domesticity is also the chance to uncover a long-hidden truth, a forgotten moment in time, or a person we never knew. For my first assignment as a virtual intern transcribing letters from the Hoffman Family collection in the Women’s History Institute at Historic Hudson Valley, I knew within the first lines that I had come across one of those treasures.

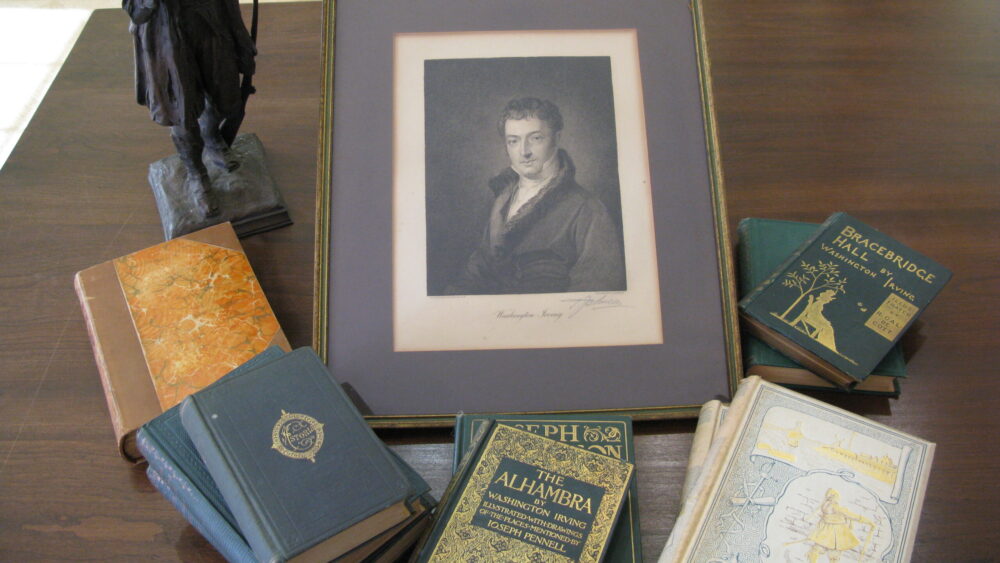

The Hoffman Family manuscript collection made its way to Historic Hudson Valley because of the family’s deep connection with the writer Washington Irving. In 1809 a young Irving was engaged to be married to Matilda Hoffman, daughter of Judge Josiah Ogden Hoffman and younger sister to Ann Alice Hoffman. Unfortunately, Matilda died of illness before they were able to wed. Despite this tragedy, the two families remained close in subsequent decades. Written many years after Matilda’s death, the six letters I had been assigned were among those sent to her sister Ann, the now widowed Mrs. Charles Nicholas, by two friends, Anicartha Miller and Elizabeth Spencer.

On October 30, 1836, Ann departed her ailing father’s New York City home with the youngest of her two adult daughters, Emma. They left little information about their destination or reason for leaving in such haste. A few months later Anicartha wrote in the first of her letters to Ann, “I went to your father’s, and to my very great surprise found that you had gone. I saw no one but Elizabeth, and she could not even tell me the name of the person with whom you had gone.” Eventually it was revealed that the pair headed “West” to reconnect with Ann’s elder daughter, Matilda, and her Baptist pastor husband in Illinois.

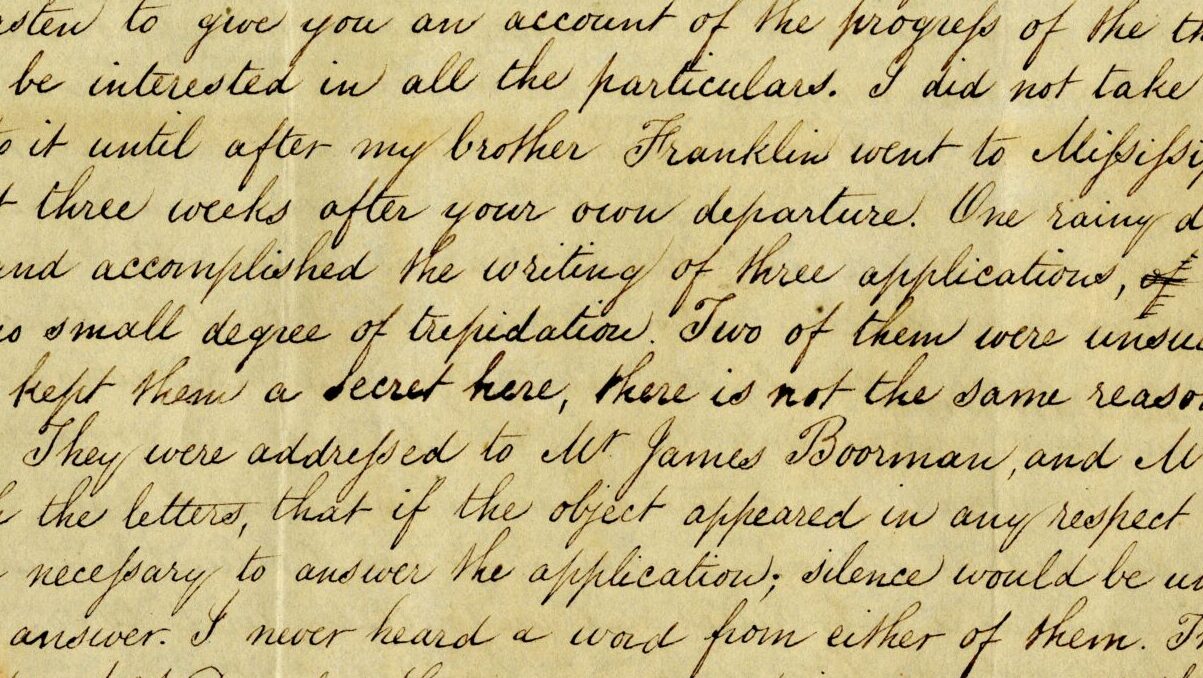

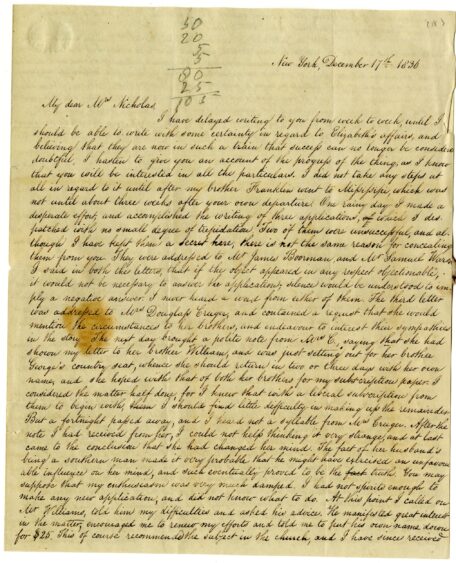

While Ann and her daughters faced a brutal western winter in their new life, Anicartha remained in New York settling “Elizabeth’s affairs.” Initially, she wrote furtively describing clandestine efforts in regard to Elizabeth:

“One rainy day I made a desperate effort, and accomplished the writing of three applications of which I dispatched with no small degree of trepidation… although I have kept them a secret here, there is not the same reason for concealing them from you… I said in both the letters, that if the object appeared in any respect objectionable, it would not be necessary to answer the application, silence would be understood to imply a negative answer.”

Quickly the letters revealed the women’s secret activity. Ann, in her absence, had entrusted Anicartha with an “unfinished undertaking”: to purchase Elizabeth’s three daughters, Rebecca, Olive and Chlorine, out of slavery. Making things more complicated was the fact that their enslavers, the George Robertson family, and the many dozens of enslaved people they owned, all resided on the Dutch-run Caribbean island of Curaҫao.

How Elizabeth herself came to be free is a mystery yet to be answered. But by 1836, she was residing in New York City – where slavery had been abolished since 1827 – in the Hoffman household along with her husband, known only as Spencer. She called herself Elizabeth Spencer. Four of my letters were from Anicartha to Ann detailing these efforts. Two letters were from Elizabeth herself to Ann expressing both her gratitude as well as her deep concern for the safety of her daughters. “As you may suppose, my mind must be very anxious about my children…” she wrote in 1838.

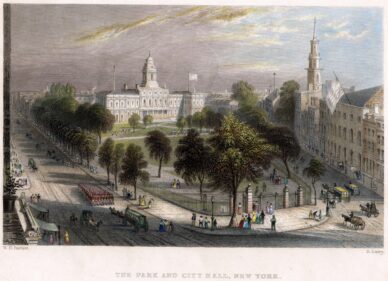

Ann Hoffman and Anicartha Miller’s strategy was straightforward: using their extensive family connections, they would raise the money needed to purchase the daughters from their enslaver. Both Ann and Anicartha – daughters of influential judges who held a variety of political positions in city and state government – had connections to wealthy New Yorkers, although neither was flush with personal funds. Along with Elizabeth, they were also recent converts to the Baptist faith, part of the Second Great Awakening sweeping the nation. A passionate faith marked by intensive religious study and frequent churchgoing was shared by all three women. We know that in early 1836 they all worshiped together at the Amity Street Baptist Church in New York City under the pastorship of Rev. William R. Williams. ![]()

Heartfelt letters about Elizabeth’s daughters were penned to some of the most affluent and powerful members of New York society. Peter Gerard Stuyvesant was among those who responded to Ann before she turned the work over to Anicartha:

“I have read with much interest the narrative of the peculiar situation of the young female slaves, which your benevolent heart so kindly communicated. Altho [sic] I cannot follow Mr. Astor’s generous example, I beg you to accept the enclosed sum of 20 dollars as a pittance towards their emancipation, and cannot doubt but Elizabeth will ultimately have cause for rejoicing, when I discover she possesses so eloquent an advocate as Mrs. Nicholas.”

Despite such successes, many of Anicartha’s appeals to her affluent acquaintances met with silence. One application to Mrs. Douglas Cruger ended in rejection when it was revealed that her Southern-born husband “was very much opposed to the emancipation of slaves,” and she was not comfortable “acting in opposition to his feelings.” Such rejections forced Anicartha to admit “that her enthusiasm [was] dampened” and she feared further failure. Unsure how to proceed, she turned to Rev. Williams for guidance, and he provided her with a strategy:

“He manifested great interest in the matter, encouraged me to renew my efforts and told me to put his own name down for $25. This of course recommended the subject in the church, and I have since received a subscription of $25 from Mr Bowen, one of $30 from the Hillys, and a promise without specifying any amount from Mr Green.”

Smaller donations came from a variety of other sources and within months of Ann’s departure “the whole subscribed [was] $295.” Anicartha’s next letter to Ann was full of confidence, stating that the matter was “now in such a train that success can no longer be considered doubtful.” Elizabeth, too, was optimistic in her correspondence, writing:

“concerning the freedom of my children… Miss Miller has succeeded wonderfully, she has made every exertion that she could to assist the poor slaves.”

They had raised the necessary funds, but the plans for Elizabeth’s daughters would not resolve so easily. Elizabeth worried, “I have written three or four letters to Curacao since you have been [gone] and have not had any answer.”

Their luck seemed to change when Quaker friend Charles Collins directed Anicartha to a shipping magnate named Joseph Foulke, as she wrote to Ann. Foulke had deep ties to Curaçao and even deeper pockets, and Anicartha reported that he “knew all about Spencer and his wife, as well as to the family that Elizabeth belongs.” Foulke agreed to forward a letter from Anicartha to Mrs. Robertson.

By the summer of 1837, a year after Ann’s first appeals, Anicartha, Ann and Elizabeth were no closer to obtaining the freedom of Elizabeth’s daughters. Despite their success of their fundraising, they didn’t seem to be able to reach an agreement with the girls’ enslavers. It was at this point that Joseph Foulke delivered some heartbreaking news from Curaçao: Mrs. Robertson had sold Rebecca.

Follow the effort to reunite Elizabeth Spencer with her daughters in Part II of “A New York Manumission Story.”

Kathryn Alexander

Virtual Intern