A New York Manumission Story From Our Manuscript Collection Pt. II

The story continues from Part I

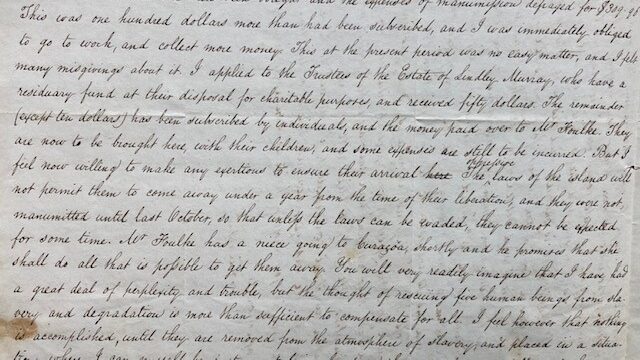

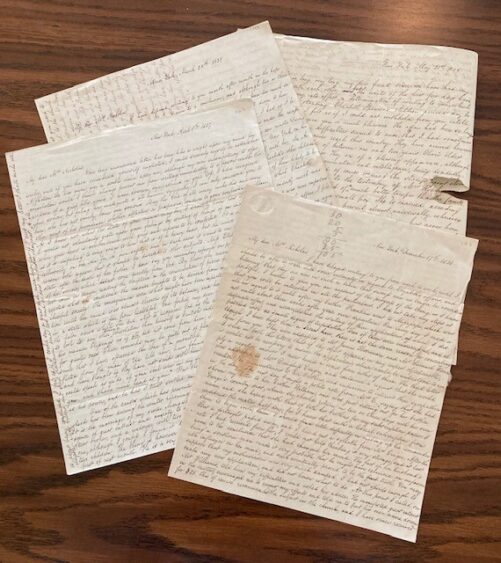

Over the summer of 1837, Anicartha Miller continued to lead the effort to manumit the three daughters of Elizabeth Spencer, a woman employed in the household of the Hoffmans who had herself become Anicartha’s friend. Previously, Anicartha had leaned upon Mr. Foulke who had some connections in Curaçao for help negotiating with Mrs. Robertson, the enslaver of Rebecca, one of Elizabeth’s daughters. Although Anicartha and Elizabeth had been disheartened to learn that Mrs. Robertson had sold Rebecca, they were later informed that Mrs. Robertson would soon pass through New York on her way to England and “would probably bring [two Spencer daughters] Olive and Rebecca both with her.” It was a shock when Mrs. Robertson and her son arrived in August bringing only Elizabeth’s third daughter, Chlorine. When the reason why the young women remained in Curaçao was shared, both Elizabeth and Anicartha were still more dismayed: “they were both of them likely to become mothers,” as Anicartha wrote: Olive and Rebecca were pregnant.

Elizabeth wrote to Ann of her fears with a delicacy that was characteristic of her time, but her meaning is clear: “the lady with whom my children lived has gone to England + left them under the care of no one + I sometimes feel afraid that what I was speaking to you of before you left here has…happened to them…[.]” Her concern was well warranted. Enslaved individuals in the Caribbean, as in the United States, were treated as property. Because of this, women such as Olive and Rebecca were extremely vulnerable to sexual abuse. At the same time, any consensual relationship they might enter into would not be legally recognized. In any case, the offspring of an enslaved woman was still considered the property of the mother’s enslaver.

At this point neither Anicartha nor Elizabeth knew that Olive already had one young child, but the difficult and unfolding situation had already galvanized Anicartha:

“The affair was now evidently much more complicated and difficult than I had anticipated at the commencement, but it was more important from the greater number of human beings involved in it… and I felt strengthened to prosecute it. “

During her layover in New York, Mrs. Robertson came to an agreement with Elizabeth Spencer and her friends to manumit Olive and “her offspring” in exchange for $186. At the same time, “Spencer paid to [Mrs. Robertson] $180 for the freedom of Elisabeth [sic].” This intriguing statement suggests that Elizabeth Spencer herself was once enslaved by the Robertson family and may have self-emancipated at a prior date before coming to live with the Hoffmans. Mrs. Robertson also agreed to leave “little Chlorine” with Elizabeth in New York. As Elizabeth wrote:

“[Chlorine] is living with me at Mrs. [Murray] Hoffman’s + it is a very great comfort + happiness to have her with me. Miss [Eliza] Miller [Anicartha’s sister] teaches her every day + has been extremely kind with her.”

Anicartha also spoke in glowing terms of Chlorine, whom she called “a child of uncommonly quick parts,” and in other correspondence she noted how quickly the young girl learned to read and write English.

During the winter of 1837, news arrived that Rebecca’s child had been born. In February 1838, Rebecca and her new son were manumitted with the assistance of Mr. Foulke. Almost two years after beginning their efforts, the freedom of Elizabeth’s three daughters, now with three grandchildren, had been achieved, but the family reunion still could not take place. Despite the fact that they were no longer enslaved, Curaçao’s brutal laws prevented Olive or Rebecca from leaving the island until “a year and a day” after their manumission. Elizabeth and Chorine continued to wait and worry. During that time, Olive gave birth to a daughter, but her eldest child also died, with no further details recorded.

In the spring of 1839, Rebecca, Olive, and their surviving children finally started for New York. After being denied passage twice (possibly on account of their race and free status), a niece of Mr. Foulke interceded with the captain of a third ship, and advanced the money for their passage. Records from Curaçao show passports for Rebecca Richard with her son Joseph and Olive Dumoulin with her daughter Betsy were issued on April 24, 1839 for travel to New York aboard the “golet Sofie.” About four weeks later, on May 21, 1839, they finally arrived in New York. Anicartha wrote to Ann Hoffman:

“Elisabeth Spencer’s children arrived day before yesterday, and I felt as if I could not withhold from you intelligence which would give you so much pleasure. The affair has been so long protracted, and so many difficulties seemed to arise, that I had sometimes feared that they would never reach this country…Elisabeth is I believe truly thankful and I think I am so myself… They are now comfortably settled in the lower part of a house in Elm street… I have no doubt of their ability to earn their livelihood, and I hope in addition to the blessings of freedom, they… may become participants in the highest benefits of a land of religious light and liberty…”

It is tempting to let the story end there; six letters that resolve so neatly. Mother and daughters free and reunited; the benevolent work well done. The Miller and Hoffman families offered all the women housing, education, and employment: a significant assistance that many formerly enslaved individuals never received. However, the jobs open to them were always in domestic service – physically demanding positions that offered limited opportunity for advancement. While Ann and Anicartha were committed to Elizabeth and her daughters’ success, later letters in the Hoffman collection suggest that not all their family members felt the same. The world outside those homes could be even more unforgiving, as the institution of American slavery began to lead the country towards Civil War.

At Historic Hudson Valley, our next task is to follow the threads to see where life in America led all these women. I’ll be pursuing this research in the collections of the New-York Historical Society, the Burke Library at Unition Theological Seminary and at Colgate University, all repositories of additional Miller and Hoffman family papers. The extended Hoffman Family archives across collections contain scores of letters waiting to be read. What was the reality for free people of color such as Elizabeth Spencer, her daughters, and her grandchildren? Did Ann Hoffman Nicholas and her daughters find their purpose in the new West fulfilled? And where did a life of faith lead an unmarried, idealistic woman such as Anicartha Miller? More work in the archives may reveal the answers.

Kathryn Alexander, HHV Women’s History Institute Virtual Transcription Project Volunteer