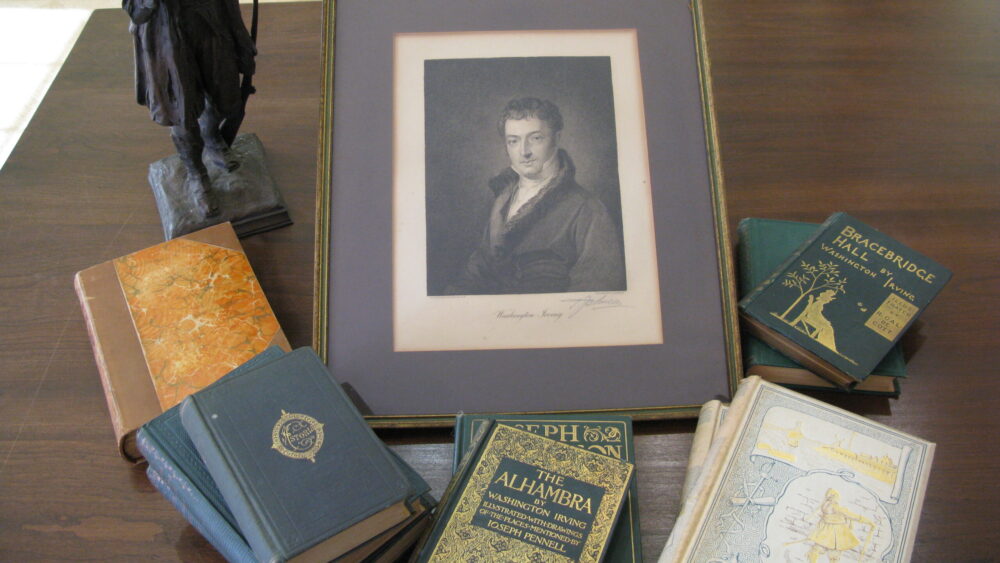

Restoring a 19th-Century Bandbox and Preserving Washington Irving’s Uniforms

Detail of newly restored bandbox

Safeguarding History: Oh, the Places We Went!

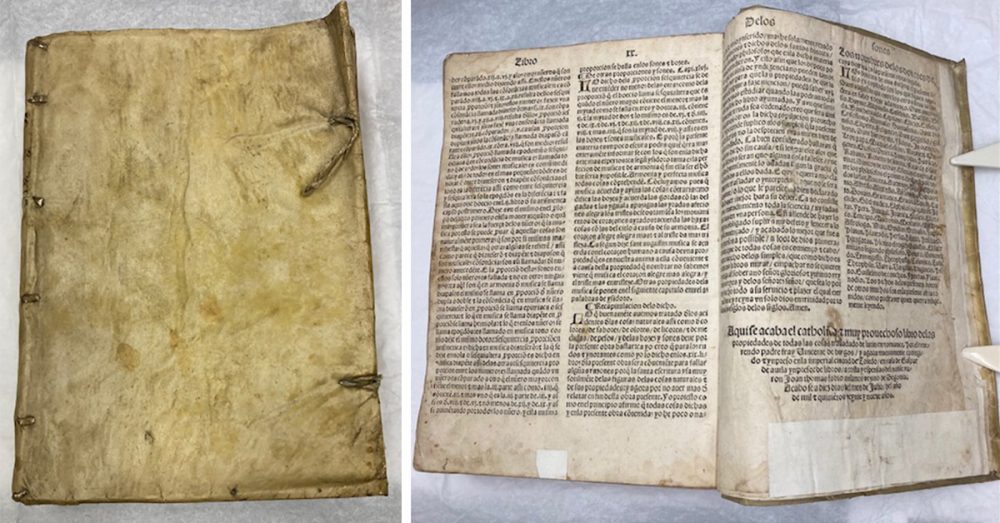

Long before suitcases had retractable handles, polycarbonate shells, and built-in phone chargers, they were made from fragile pasteboard and covered with decorative papers. Only a few of these bandboxes survived to tell us about the people who made them or the journeys they took.

One of those rare cases from the 1830s, newly restored with funds from the New York State Council on the Arts/Greater Hudson Heritage Network Conservation Treatment Grant Program, will be on view in May when Washington Irving’s Sunnyside reopens to the public. Placed in the second-floor bedroom used by Irving’s nieces Sarah and Catharine, it will be a focal point for guides and visitors to discuss the young women’s educations at Emma Willard’s Troy Female Seminary and their frequent travels along the Hudson River.

An image of a ship adorns the bandbox, along with a topical political reference to the Tariff Act of 1828 that targeted imported materials like wool and fur used to make the clothing carried in such a box: “Prosperity to our Commerce and Manufacturers.”

Female entrepreneurs were responsible for most bandbox production, including the prolific Hannah Davis who had a workshop in Jaffrey, NH. The New York City business directory of 1840 lists no fewer than four bandbox paper manufacturers, a sign of a thriving cottage industry.

And Speaking of Packing

Two of Washington Irving’s diplomatic uniforms have been moved to individual high-quality archival storage boxes to preserve them for future research and possible online exhibitions. One of the uniforms was likely worn during Irving’s time as the minister to Spain (1842–1846). It has long trousers that can now lie flat to prevent damage from folds, Paris-made buttons, and significant metallic gold embroidery around the collar and center front. The other is less ornate, likely worn when he was in a junior position as the secretary of the United States delegation in London (1829–1832).

The storage boxes, purchased with the help of another GHHN grant, have also re-housed a fragile Van Cortlandt family quilt dating to the 1790s with a chintz center field and ribbon-pattern chintz border. Linen bedsheets, with the monogram P.V.C. in either fine embroidery or ink, have new storage as well. They belonged to either Pierre Van Cortlandt (1721–1814) or to his son Pierre Van Cortlandt II (1762–1848). The sheets certainly were laundered, pressed and “turned” at Van Cortlandt Manor (the annual process by which the long center seam was cut and the two narrow halves re-sewn together for even wearing), work that would have been done by Sibby, Abby, and the other enslaved women there. The fine stitches preserved in these linens may well be a small bit of evidence that remains of their skilled labor.